Afterlives of Lekra: Authoritarian Regimes and the Erasure of Bandung’s Spirit

Turang (Comrade, 1957), a film by Lekra (Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakyat/ People's Cultural Institute)-affiliated artist Bachtiar Siagian, was banned and its creator exiled and imprisoned under Soeharto’s authoritarian regime. Screened on 24 April 2025 at the Barbican Centre, London as part of the Cinema Restored strand curated by Matthew Barrington, the film portrays the anti-colonial struggle in Indonesia, and, as reflected upon in the first part of this essay, emphasises collective care as essential to sustaining resistance, in alignment with the spirit of Bandung. However, this was deemed subversive and threatening by Soeharto's New Order government—revealing the regime’s deep intolerance toward radical cultural expressions. The second part of this essay examines the systematic erasure of Indonesia’s radical cultural history in the political context surrounding the rise of Soeharto’s repressive regime. It also explores the enduring legacy of this repression, which continues to shape Indonesia’s cultural and political landscape even after Soeharto’s fall in 1998 through a popular democratic movement.

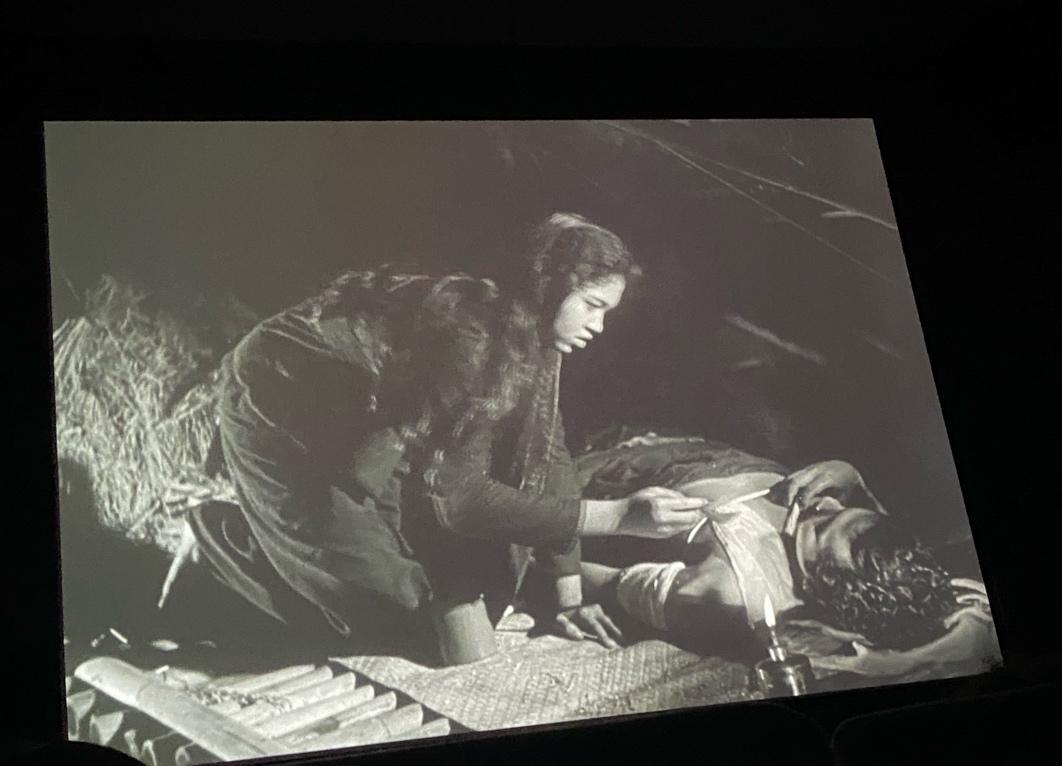

Tipi cares for a wounded guerrilla fighter. (Still from Turang [1957] by Bachtiar Siagian. Image courtesy of the author.)

Stylistically, Turang exemplifies the social realist mode favoured by many Lekra-affiliated artists. Its portrayal of women is particularly nuanced. On the one hand, the film highlights often-invisible forms of the labour of social reproduction—caring for the wounded, cooking, laundering and child-rearing—that are essential to any prolonged struggle. On the other hand, it affirms conventional gender roles which tends to limit women’s agency. Tipi, the lead female character, is portrayed primarily as obedient—following instructions from her father and the guerrilla leader, seldom engaging in strategic dialogue. This portrayal is somewhat disappointing, as social realism not only reflects social realities but also reinforces existing social norms—legacies that continue to persist. Nevertheless, it does not undermine the film’s broader critique of colonial domination or its importance as a work of political cinema that centers common people as its primary subject.

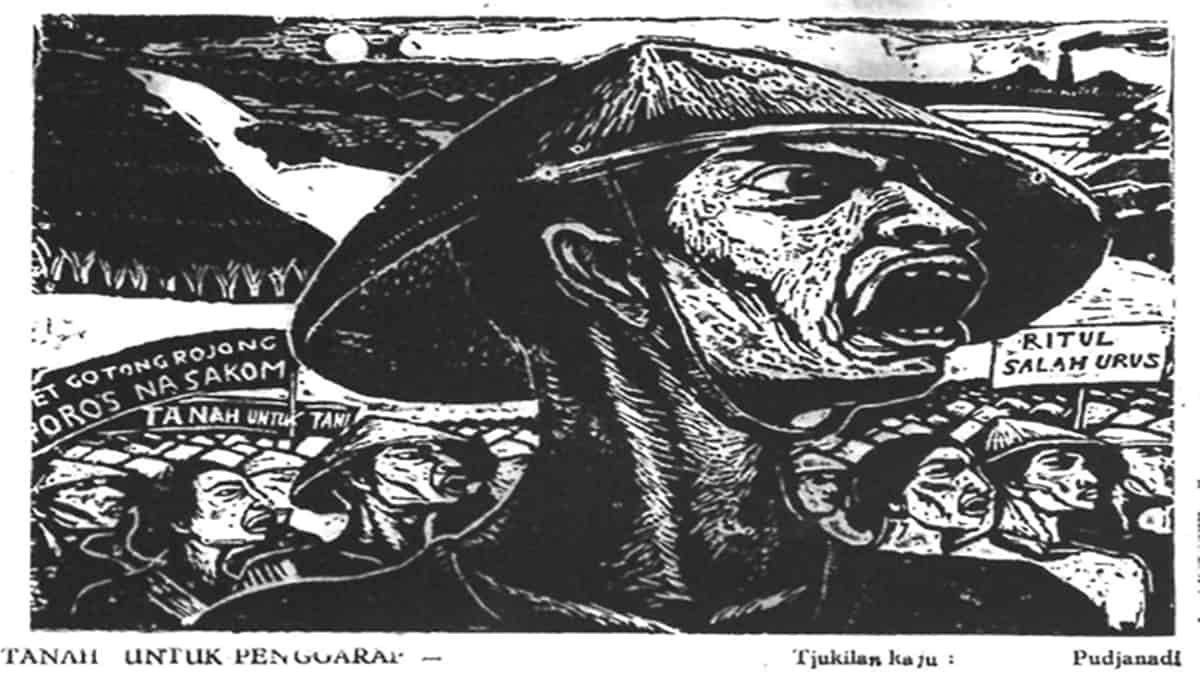

One of the sketch works on woodcut entitled “Land for Cultivators” created by Pudjanadi, a Lekra artist. (Image Source: https://www.harapanrakyat.com/2022/09/sejarah-lekra-lembaga-kebudayaan-pendulang-massa-pki/)

Siagian’s artistic vision is inseparable from his involvement in Lekra, which championed the view that culture must serve the people. Across mediums—film, literature, painting, performance, etc.—Lekra artists shared a common mission: to centre the lives, struggles and aspirations of working people. As stated in the organisation’s 1957 document, Introduction and Basic Regulations, which was inaugurated in their first congress: “The people are the sole creators of culture, and the development of a new Indonesian culture can only be carried out by the people.” This philosophy permeates the film, despite filmmaking’s logistical and financial burdens, and the film remains committed to portraying the lives of workers, peasants and women as central—not peripheral—to the national narrative.

Bachtiar Siagian. (Image source: Wikipedia)

In our phone interview, Bunga noted that Bachtiar was among Lekra’s most prolific filmmakers. He continued making films until 1965, including Daerah Hilang (The Lost Area, 1956), which tells the story of the forced eviction of a working-class neighbourhood in Kemayoran Lama, Jakarta—an act of spatial dispossession rooted in colonial urban planning that was perpetuated by postcolonial authorities. Creating politically engaged cinema, however, was not easy. Unlike literature or theatre, film required substantial resources. Filmmakers like Bachtiar were thus challenged to create works that were both ideologically potent and economically viable.

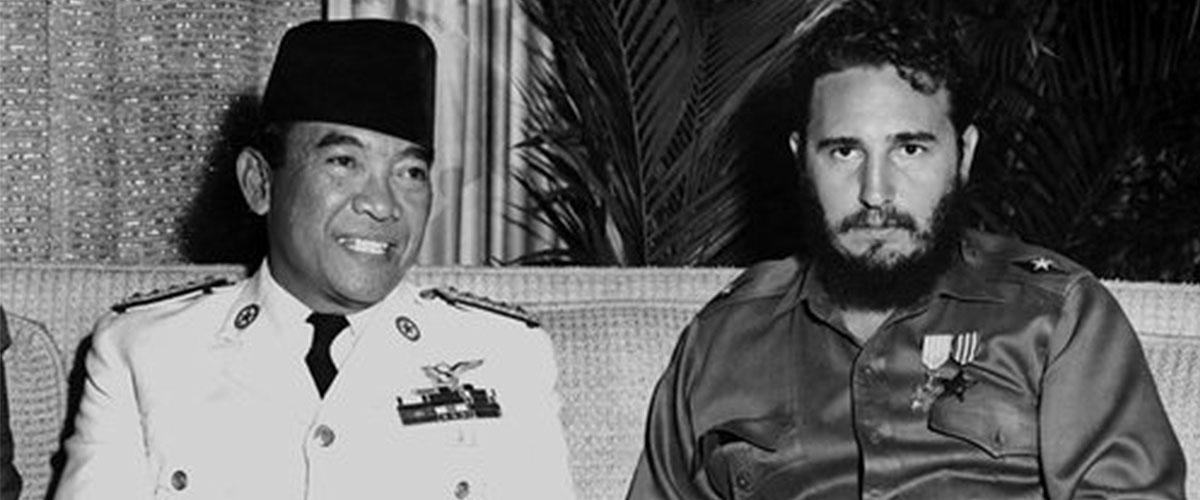

The cultural revolution that Lekra envisioned came to a violent halt following a tragedy after the 30 September 1965 incident—when several military generals under then President Soekarno’s regime, allegedly aligned with capitalist interests of the United States, were kidnapped and killed in the name of protecting Soekarno. While Soekarno distanced himself from the movement, Soeharto took advantage of the political instability to orchestrate an anti-communist purge. Thus, the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), then the world’s largest communist party outside China and the USSR, was blamed and accused of orchestrating a coup, and what followed was a campaign of mass violence, repression and massacre. Members of the PKI and affiliated organisations, including Lekra, were persecuted, exiled and massacred—with the complicity of right-wing civilian militias, beside the Indonesian military afterwards. As per estimates, between 500,000 and one million people were massacred. President Soekarno, who was a left sympathiser and championed the non-aligned movement, was replaced by Soeharto, whose three-decade rule violently erased Indonesia’s radical cultural history. Subsequent research later revealed that the 1965 tragedy was part of a CIA operation by the United States.

Soeharto, one of the cruelest dictators in the world, known as "the smiling general." (Image source: https://artsandculture.google.com/entity/m01fvnh?hl=it)

Under Soeharto’s authoritarian regime, anti-colonial artworks by Lekra artists, including Turang, were banned and systematically suppressed. Soeharto’s New Order was not only anti-left but also aggressively anti-intellectual and anti-historical, fostering a collective amnesia that persists to this day. The suggestion that Soeharto be named a national hero re-emerged recently, underscoring just how little reckoning has occurred. In this hostile climate, recovering films like Turang is not merely a curatorial act—it is a political intervention. As Bunga Siagian rightly observed and told me in our phone conversation: “Film is not just material; it is culture.”

Turang stands as a cinematic echo of Bandung’s spirit, which championed the struggle for independence among colonised nations, a testament to the convergence of the global leftist and anti-colonial anti-imperialist visions. In today’s Indonesia, where leftist scholarship is marginalised, the recovery of such films is vital. As Bunga emphasised in our phone conversation, “Being aware of world film history is crucial.” A transnational network of researchers, curators and archivists is needed to locate and restore the many exiled works which remain scattered across the globe. As in Indonesia’s context, the Indonesian state, represented by the Ministry of Education and Culture, has done little to support this effort. According to Bunga, this ministry “has never formed a dedicated team to recover these lost cinematic works.” In this context, the rediscovery and restoration of Turang is both a cultural milestone and a political act. It is not merely a recovered film, but a recovered memory—a fragment of Indonesia’s radical imagination brought back from exile.

Soekarno and Fidel Castro in Havana, Cuba, 1960. (Image source: https://historia.id/histeria/articles/sukarno-dan-jenggot-fidel-castro-vgX7k/page/1)

To read the first part of this essay, click here.

To learn more about art influenced by the spirit of Bandung, read Ankan Kazi’s essay on Suneil Sanzgiri’s At Home But Not At Home (2019), Madhubanti De’s reflections on the presentation on Sirens of Modernity (2022) by Samhita Sunya and ASAP | art’s public talk featuring Kristine Khouri titled “The Political Imagination of Art” (2024).