Turang: On Cultural Revolution and People’s Liberation Struggle in Indonesia

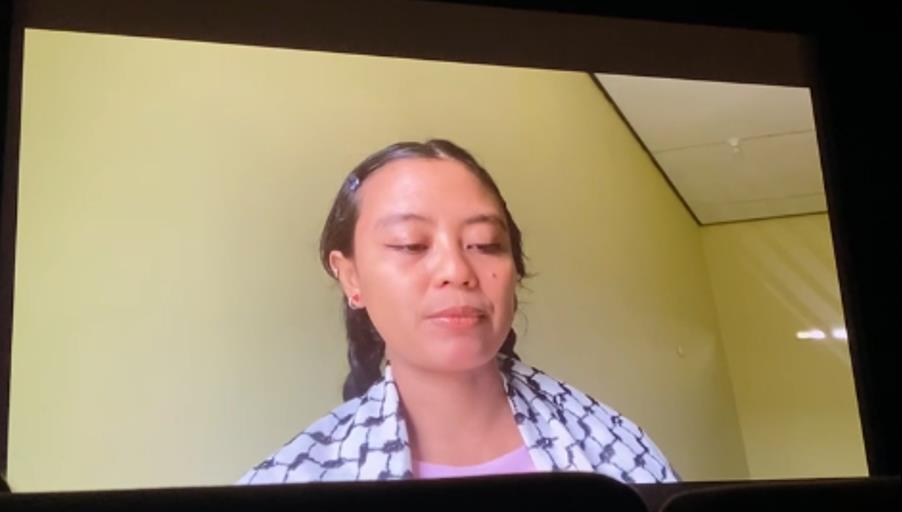

Bunga Siagian, wearing a Palestinian keffiyeh, gave an online introduction before the screening of Turang at the Barbican Cinema, London. The keffiyeh, symbolising solidarity with Palestine, aligns with the spirit of Bandung. (Image courtesy of the author.)

Turang (Comrade, 1957) is a long-lost Indonesian film by leftist director Bachtiar Siagian, whose work and life were violently disrupted by Soeharto’s New Order regime. Siagian, imprisoned without trial and later exiled, was one of many artists affiliated with Lekra (Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakyat/ People's Cultural Institute)—Indonesia’s most prominent left-wing cultural organisation before its annihilation in 1965. Remaining undiscovered for decades, this black-and-white film was created just two years after the 1955 Asia-Africa Conference (AAC) in Bandung (often known as the Bandung Conference)—a defining moment in the global anti-colonial and anti-imperialist movements. First screened at the 1958 Asia-Africa Film Festival in Tashkent, the film resonates with the conference’s ethos of non-alignment and cultural sovereignty. It was rediscovered through Gosfilmofond, the Russian film archive in Moscow, thanks to the efforts of Bunga Siagian, a film researcher and the director’s daughter, who found Turang through her research and support of her international cultural and academic archivists’ network.

Appropriately, it was screened on 24 April 2025, at the Barbican Cinema in London, exactly seventy years after the Bandung Conference. The screening was part of the art of the Barbican’s Cinema Restored strand curated by Matthew Barrington. Cinema Restored is a bi-monthly film strand that looks at recently restored items of often politically infused global cinema, drawn from the excellent work done by cinema archives and restoration laboratories. Before Barbican, Turang was also screened at the Rotterdam International Film Festival.

Hidden bullets among the salt sacks. (Image courtesy of the author.)

The film opens with a deceptively serene scene: two men in a bullock cart travel to a bustling market to buy salt. Their journey back is equally tranquil—until a quiet revelation shifts the tone. Hidden in their cart’s cargo are bullets, cleverly concealed among the salt sacks. Kembaren and Rusli, two men of Karonese ethnicity from North Sumatra, are not only villagers; they are guerrilla fighters engaged in Indonesia's anti-colonial struggle. This early twist encapsulates the film’s central idea: that resistance is not always heroic in appearance but deeply embedded in the making of everyday life.

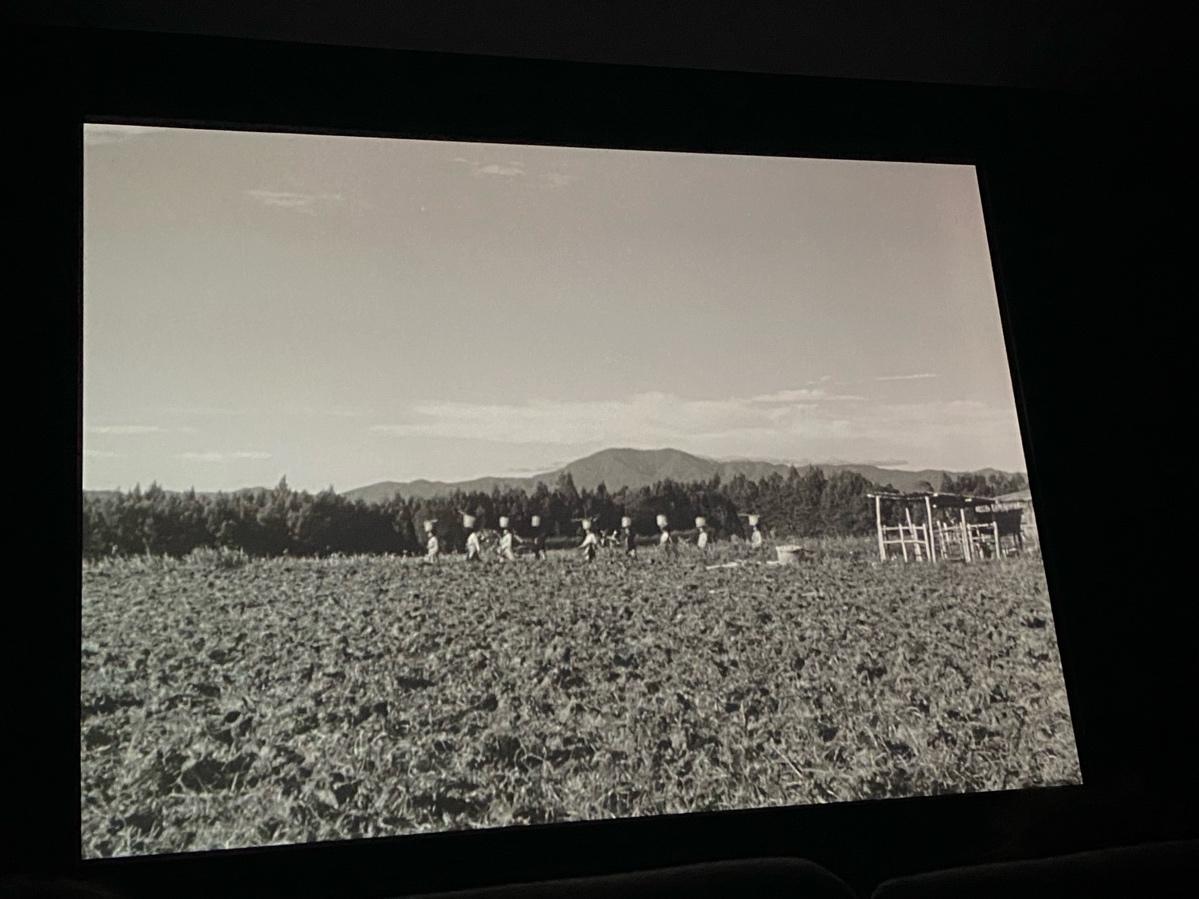

One of the wide landscape shots in Turang. (Image courtesy of the author.)

The film’s aesthetics are laced with symbolism. Dutch soldiers who are not ethnically Dutch and internal traitors among the village residents—these elements remind viewers that colonialism is not merely a question of identity but one of ideology and allegiance. The wide landscape shots capture the grandeur and beauty of anti-colonial struggle. One of the shots, depicting the landscape and people marching before tending the crops, highlights the often-unseen labour done by people in nurturing the lands they inhabit. The shot evokes the scale of the struggle, underscoring the inseparability of land, people and liberation.

Villagers tend crops together. (Image courtesy of Sarah Harvey.)

At its core, Turang is a film of grassroots anti-colonialism, where survival through collective care is central. Its narrative is modest: a group of guerrilla fighters resist the armed Dutch colonial forces who possess far more advanced weaponry, but its resonance lies in its attention to the life of ordinary people. Siagian foregrounds not just the armed struggle, but the unseen labours which make it possible: the village residents who shelter, feed and sustain the fighters, often at great personal risk. These acts of solidarity—refusing to divulge the fighters’ whereabouts, tending crops and maintaining daily labours and activities—are at the heart of the film.

This focus on collective care and survival imbues Turang with a quiet radicalism. Scenes of village residents dancing, planting rice, cooking and celebrating traditions are more than cultural texture; they are assertions of dignity under colonial occupation. Early in the film, a joyful dance sequence recalls Emma Goldman’s oft-quoted phrase: “If I can’t dance to it, it’s not my revolution.” In Turang, cultural life is not a distraction of the revolution—it is the revolution.

Part two will elaborate on the political context of Indonesia's authoritarian regime, which led to the banning and exile of Turang as a radical cultural product.

Guerrilla fighters sing a resistance song together with the village residents. (Image courtesy of Sarah Harvey.)

To learn more about films exploring anticolonial and postcolonial struggles, read Arundhati Chauhan’s essay on Suneil Sanzgiri’s Two Refusals (2023), Ankan Kazi’s reflections on Dharmasena Pathiraja’s Bambaru Avith (1978) and Koyna Tomar’s essay on Ritwik Ghatak’s Amar Lenin (1970).

All images are stills from Turang (Comrade, 1957) by Bachtiar Siagian unless otherwise mentioned.