The Lamenting Waterfall: On Shilpa Gupta’s Practice

I first came across Shilpa Gupta’s work through video documentation of her famous multimedia installation For, In Your Tongue, I Cannot Fit (2017–18), first displayed at the Venice Biennale in 2018. One hundred microphones loomed in the background as each poet’s voice emerged from the printed pages of text that were held by metal stands. The poem “Oh Waterfall, Why Are You Lamenting?” by Zeb-un-Nissa, the daughter of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, is included in this collection of poems:

Oh waterfall, why are you lamenting?

At whose remembrance did grief wrinkle your face?

What was your pain that all through the night

You kept striking your head on the rocks,

Shedding tears?

Over 400 years ago, Zeb-un-Nissa encompassed today’s world of grief and lament with the imagery of a waterfall and its immense force on the rocks below. Gupta’s practice has been dedicated to holding and depicting such grief in various forms incorporating sound, neon lighting, photographs, drawings and participatory creative exercises grounded in research. Spending time with such moments of grief at her solo exhibition—organised by Vadehra Art Gallery at Bikaner House—made me realise that her works were even stronger in person.

Installation view of Listening Air as part of Shilpa Gupta: Lines of Flight at Ishara Art Foundation, 2025. (Shilpa Gupta, 2019-22. Multi-channel sound installation, speakers, microphones, lights, printed text on metal stands. Dimensions variable, site-specific, 25-minute loop. Image courtesy of Ishara Art Foundation and the artist. Photography by Ismail Noor/Seeing Things.)

Listening Air (2019–22) at Bikaner House was a multi-channel sound installation with speakers, microphones, lights and printed text on metal stands reminiscent of For, In Your Tongue, I Cannot Fit. As I walked through the metal stands in a pitch-dark room, I was unexpectedly confronted by a microphone which would broadcast songs like “Bella Ciao” by silenced women rice weeders in Po Valley of Italy in the 1940s and by farmers during a sit-down protest in Delhi in 2020; “We Shall Overcome” by tobacco workers in South Carolina; as well as “Hum Dekhenge,” penned by Faiz Ahmed Faiz in the late 1970s as a symbol of hope in Pakistan and India. As each voice filled the room, it became an atmosphere of grief, lament and loss. Listening Air also offered reprieve to me as the voices were soothing, reminiscent of hope, calm and our earthly uncertain presence in the universe. Gupta suggests how sunrise and sunset would come and go, in spite of the emotional overwhelm of territorial conflicts and associated acts of silencing remaining unchanged in their dark lividity.

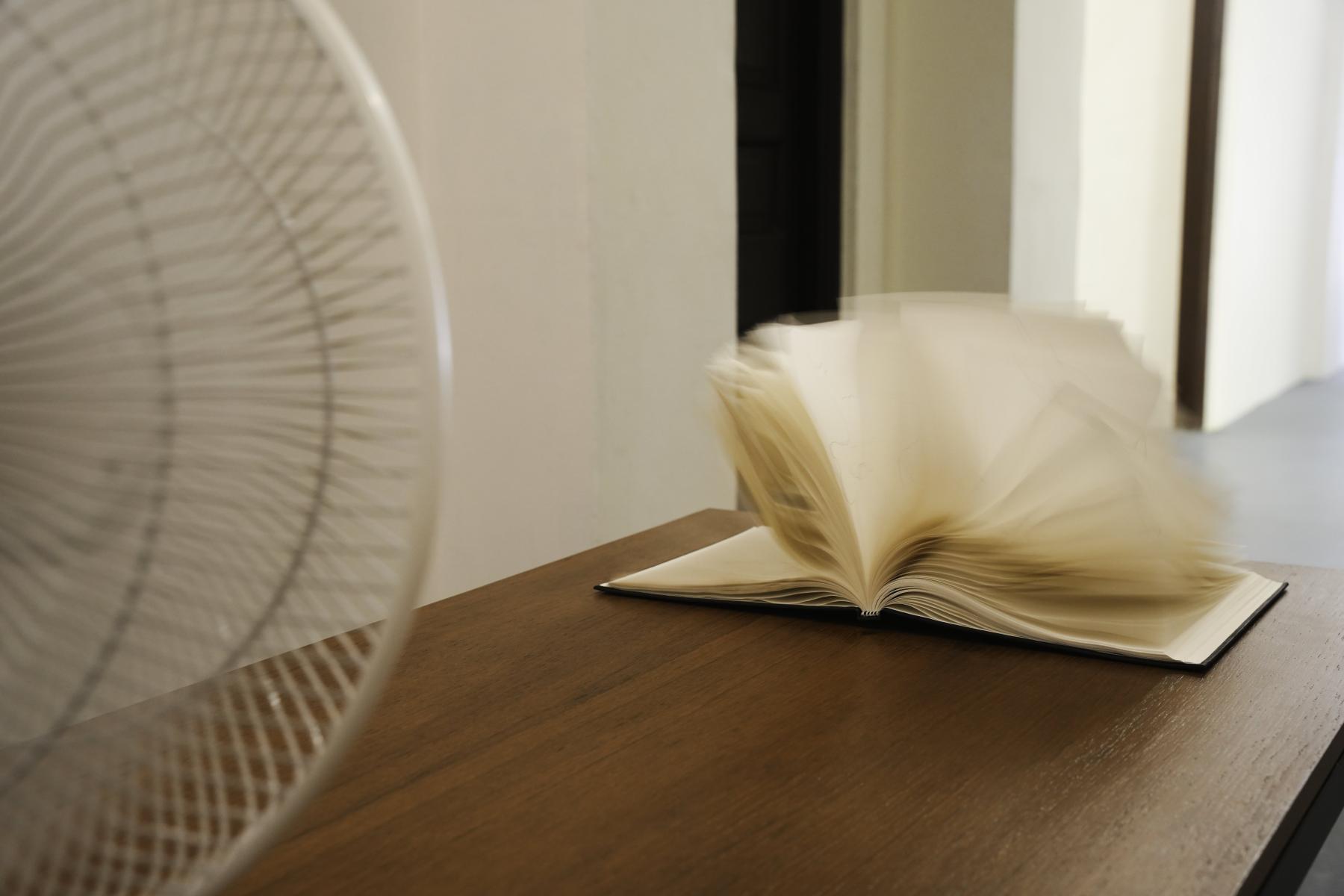

Installation view of 100 Hand Drawn Maps as part of Shilpa Gupta at Bikaner House. (Shilpa Gupta, 2007-08. Table, fan, and book, 106.7 x 61 x 122 centimetres. Image courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery and the artist.)

These silences of territorial conflicts surround Gupta’s practice in terms of rethinking and recording the post-Partition ruptures among India, Bangladesh and Pakistan. 100 Hand Drawn Maps of India (2007–8), a book displayed on a table with a fan, was the most intriguing work for me. The book consisted of drawings of a map of India from memory by 100 people on fragile, low GSM paper. As I stood in front of the installation, trying to get an extended look at one or two drawings, I failed due to the fast winds from the fan and a fear of damaging the book. The fragility of the book’s pages represented the fragility of something much larger: disappearing memories, definitions, and administrative powers’ expectation for people’s ultimate surrender to nation states and their prescribed borders. Does forgetting one border or one line in their map drawing make someone less of a citizen of a nation state? Does it make them less patriotic and less worthy of the privileges of being a citizen? Attempts to answer this question are emblematic of collective grief and a longing amongst people for reconciliation and the reign of social justice—especially with aspects that legal justice does not cater to.

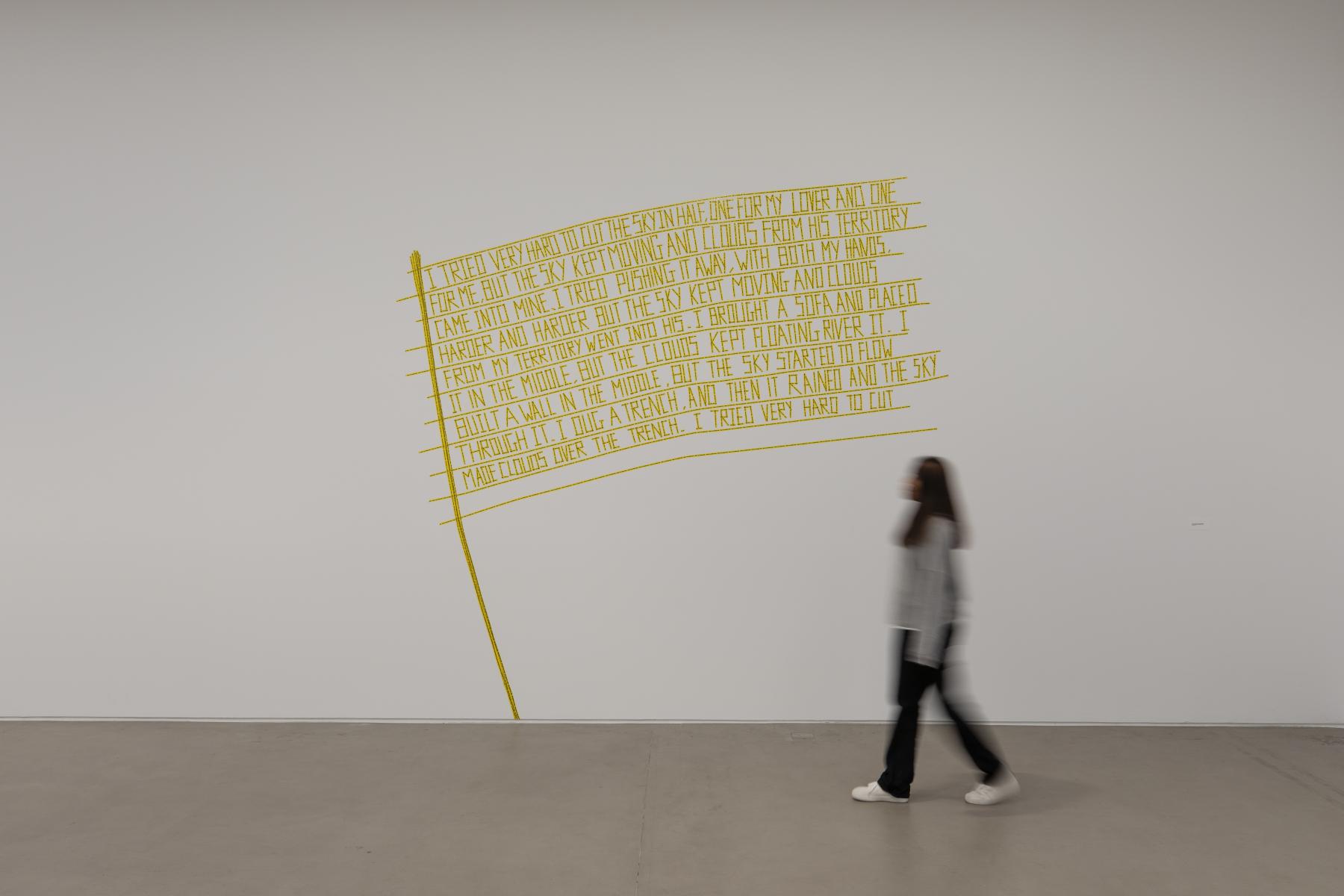

Installation view of "There is No Border Here" as part of Shilpa Gupta: Lines of Flight at Ishara Art Foundation, 2025. (Shilpa Gupta, 2005-06. Wall drawing with self-adhesive tapes, 300 x 300 centimetres. Image courtesy of Ishara Art Foundation and the artist. Photography by Ismail Noor/Seeing Things.)

This longing is expounded further in Gupta’s display of “There is No Border Here” (2005–06) in Lines of Flight. Currently on view at the Ishara Art Foundation in Dubai until 31 May 2025, the work appears as a 3 x 3 metre wall drawing with self-adhesive tapes as it takes the macro form of a national flag flowing in the wind. In this piece, Gupta narrates a mundane, micro-moment of trying to divide territories between her and her lover in the sky. In this ultimately disappointing exercise done in the vastness of the sky, she and her lover are unable to agree on their individual territories. She describes it as sofas, hands, or trenches being unable to keep clouds from moving from one person’s territory to the other’s. This installation urges viewers to imagine a free, almost utopian world without state-imposed territories and boundaries—especially those that manipulate religious, ethnic and cultural ideologies to suit political agendas. The marks made by the self-adhesive tape remain, even after the display is taken down, much like the undefinable territories that Gupta highlights in the work.

While walking through the exhibition at Bikaner House, grief and loss connected to the borders between India and Bangladesh became particulary potent through the series Unnoticed (2017). The work comprises C-prints of a photograph taken on the India-Bangladesh border with motor parts from informal trade partnerships between the two countries pasted on. The images take on a three-dimensional form even as they continue the reference to the sky as a never-ending non-territorial space. The artist poses several questions: Does the sky also divide itself at the border that separates India and Bangladesh? Who has access to both sides of the border? And most importantly, just like these motor parts traverse both sides ‘informally’, how many people were moved and displaced post-Independence when the India-Bangladesh border came into being?

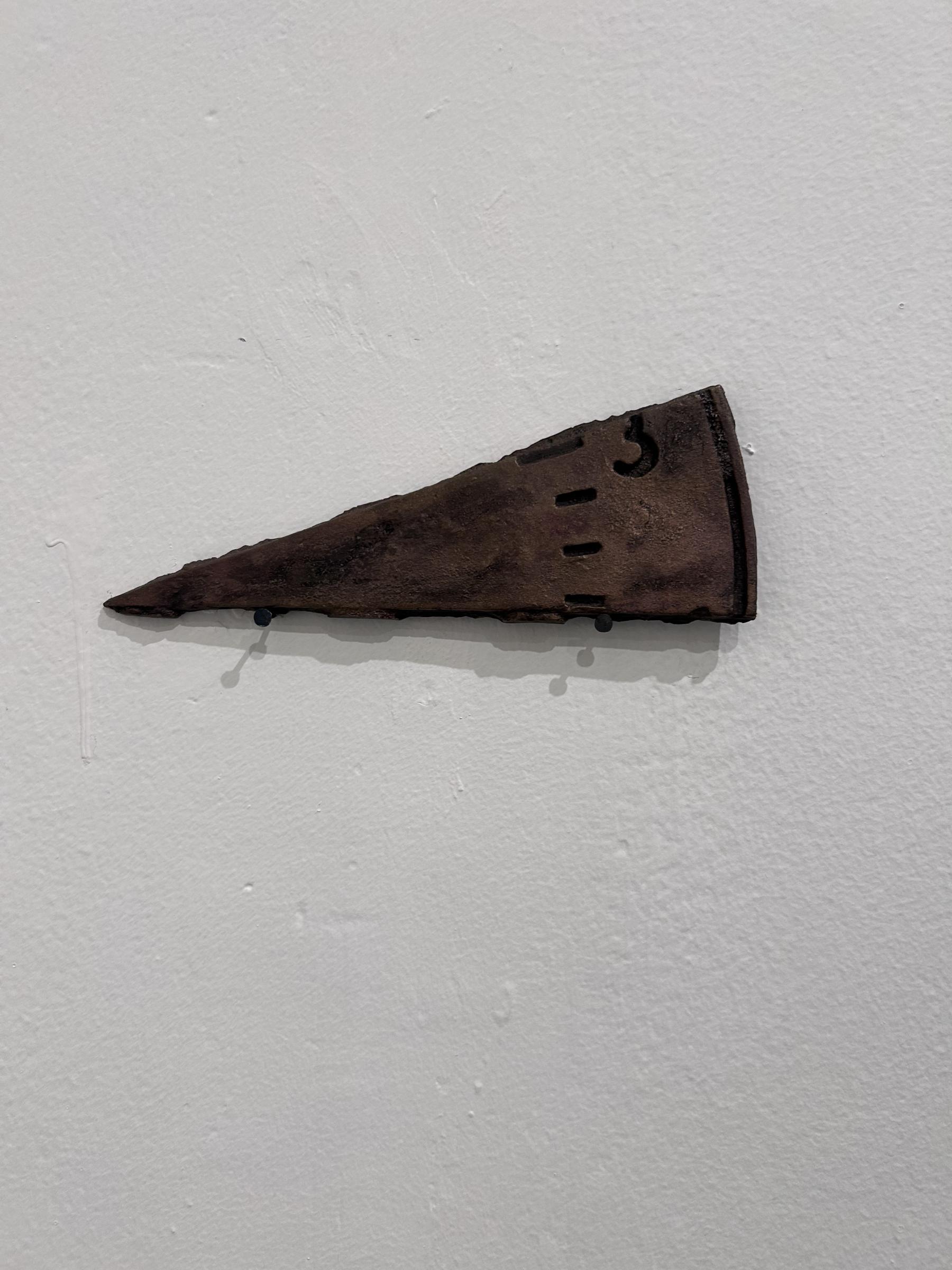

Installation view of Visitor Hours at Bikaner House. (Shilpa Gupta, 2021. Gunmetal, 120 x 0.5 x 7 centimetres. Image courtesy of Pramodha Weerasekera and the artist.)

Certain object-based works displayed in Gupta’s most recent solo exhibitions invoked fear in addition to grief. Gunmetal powder and glass, as well as barely harmful pencil points used in several artworks, evoke indescribable pain and memories for many who have lived through wars and border conflicts. These objects and their impact are all too familiar for many of us in South Asia. As chaos reigns with genocidal wars, Gupta’s works encourage a slowing down to rethink such conflicts and to influence the affective realm of normal people—engaging with anger, guilt, disappointment, fear and, most importantly, grief. For as Gupta reminds us through her practice of almost three decades, much like the waterfall’s tears strike heavily on the nearby rocks, territorial conflicts and oppression, as well as the direct or indirect silencing of persons and communities, take an emotional toll on all.

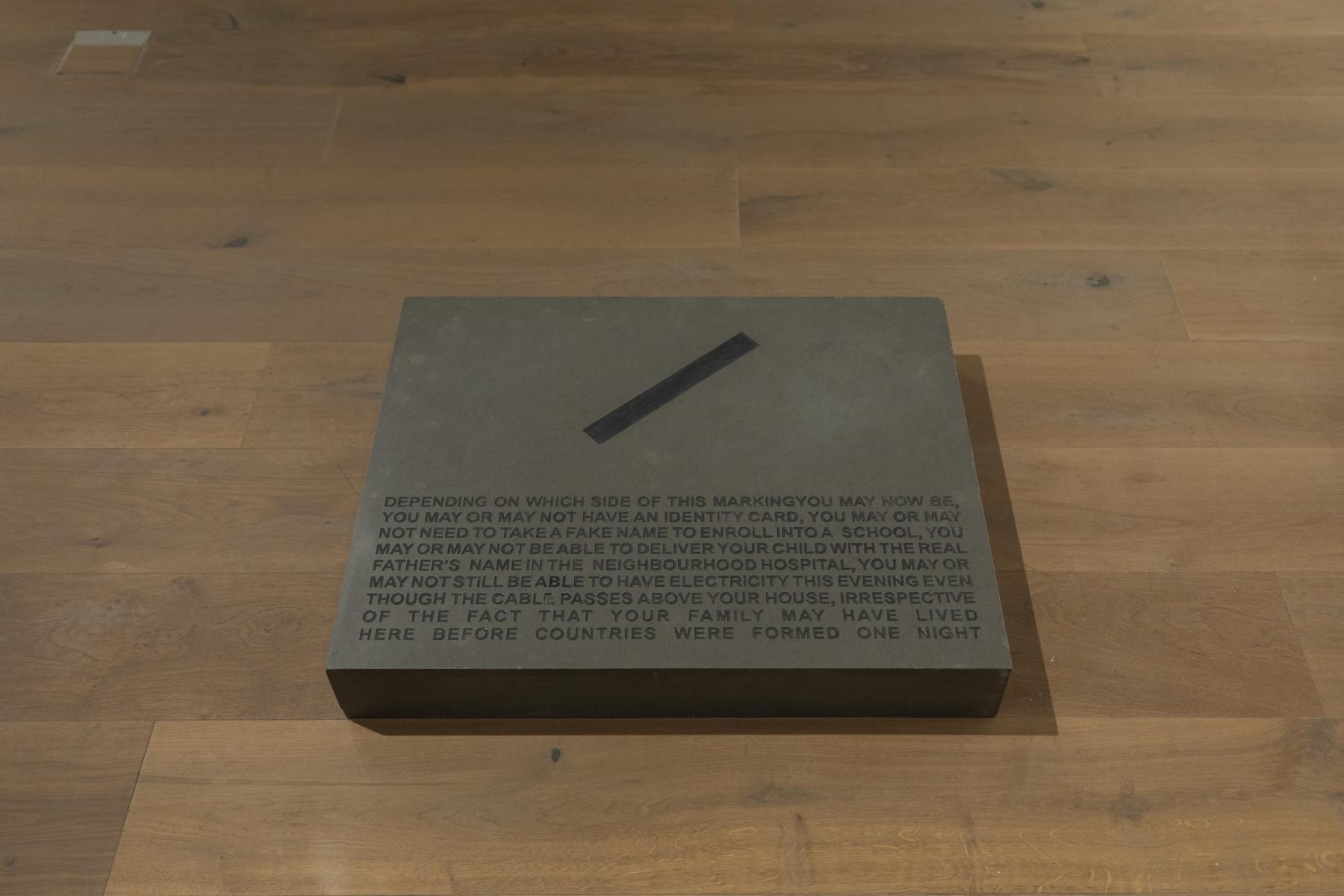

Installation view of Untitled as part of Shilpa Gupta: Lines of Flight at Ishara Art Foundation, 2025. (Shilpa Gupta, Engraving on stone, 55 x 69 x 10 centimetres. Image courtesy of Ishara Art Foundation and the artist. Photography by Ismail Noor/Seeing Things.)

Shilpa Gupta is the 2025 recipient of the Asia Arts Pathbreaker Award, given annually by the Asia Society India Centre.

To learn more about the recipients of this year’s awards, read Adreeta Charaborty’s conversation with Anupam Sud. To learn more about previous recipients, read Santasil Mallik's two part interview with Prasiit Sthapit, who won the Asia Arts Future Award (South Asia) in 2024 as well as interviews with the winners of the 2022 edition which includes Himmat Shah, Jasmine Nilani Joseph and Sumakshi Singh. Also revisit the ASAP | art podcast in which Najrin Islam speaks to Inakshi Sobti, Chief Executive Officer of the Asia Society, India.