Between Valour and Prejudice: Chhaava, Maratha History and Marathi Cinema

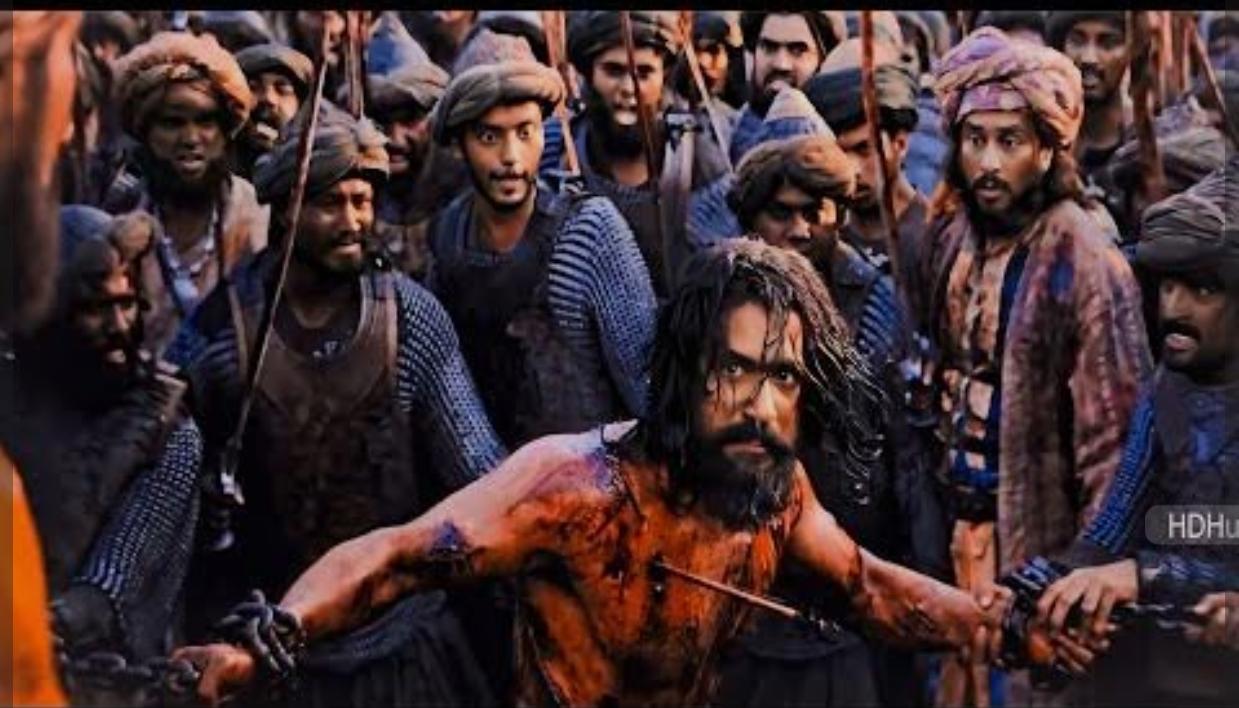

Chhaava highlights the courage and charisma of Chhatrapati Sambhaji, avoiding the earlier portrayals that emphasised his repentance. Unlike pre-1990s films, it focuses solely on his role as a protector of religion (Dharmarakshak). (Image courtesy of director Laxman Utekar.)

The recent Hindi-language film Chhaava (2025) directed by Laxman Utekar tells the story of Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj, the son and successor of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, the founder of the Maratha Empire. Known for his fierce resistance against Mughal expansion under Emperor Aurangzeb, he is often remembered for his unwavering defiance in the face of torture and death. While nineteenth- and twentieth-century literary narratives celebrated Sambhaji as Dharmarakshak (Protector of the Hindu Faith), recent public discourse, especially since the 1990s, has increasingly embraced the more inclusive title Swarajyarakshak (Protector of Self-rule), reflecting a subtle shift in how his legacy is interpreted. However, films like Chhaava suggest an existing tussle between the two interpretations.

Technically refined and stylistically innovative, Chhaava is deeply influenced by the aesthetic and ideological framework of Marathi historical cinema, particularly its portrayal of Maratha valour, regional pride and Mughal antagonism, which were discussed in the first part of this essay. Aurangzeb is presented through a heavily stylised lens as a tyrannical figure, while Mughal forces are coded through clichéd visuals and a moralising tone that casts Muslims as perpetual aggressors. Earlier Marathi films such as Chhatrapati Shivaji (1952) and Dhanya Te Santaji (1968) had also portrayed Aurangzeb in a demonised fashion. By mirroring older moral sermons that infantilise Muslims by regarding them as incapable of rational statecraft or cultural sensitivity, Chhaava reinforces a deeply flawed historical understanding.

Chhaava portrays the Mughals as obsessed with religion, but many prominent Marathi historians argue that Chhatrapati Sambhaji’s torture was not solely due to his refusal to convert to Islam. (Image courtesy of director Laxman Utekar.)

The movie portrays Sambhaji’s turbulent journey as a warrior, scholar and statesman, focusing on his fierce resistance against the Mughal Empire, particularly Emperor Aurangzeb. It highlights his commitment to protecting the Maratha Swarajya and his refusal to convert to Islam. Chhaava thus seeks to present Sambhaji not just as a martyr but as a figure navigating the challenges of empire, faith and resistance. The film’s commercial success reignited public discourse around Aurangzeb and the Mughal Empire, which quickly turned polarising across Maharashtra, leading to heightened communal tensions. In an extreme reaction, some fringe elements began demanding the demolition of Aurangzeb’s tomb, an Archaeological Survey of India-protected heritage site, reflecting how historical narratives—when framed through a narrow lens—can be weaponised to fuel divisive politics.

To understand Chhaava, it is crucial to situate it within the broader trajectory of Marathi historical cinema, which began to experience a noticeable decline after economic liberalisation in the 1980s and 90s. Increasing commercialisation of cinema in this period began to cater to an urban, aspirational middle class. Box office success became the key metric, pushing filmmakers to focus on high returns and mass appeal. Simultaneously, the Mandal Commission report reshaped Indian politics by empowering backward caste groups as it challenged upper-caste dominance. The rise of OBC-based regional parties marked a new phase of identity politics, especially in northern India. This trend is reflected in movies produced in the 2000s and 2010s wherein a handful of Marathi filmmakers began experimenting with social themes. Thus, films such as Fandry (2013), Sairat (2016), Deool (2016), Court (2014) and Tumbbad (2018) played a crucial role in shifting the cinematic narrative by exploring caste, class and rural life. This indicated a gradual, though cautious, willingness to engage with broader transformations in regional politics and cultural discourse as it marked a subtle departure from the formulaic and ideologically rigid narratives of earlier decades. While Chhaava is attentive to the changes in Marathi cinema since the 2000s, such as technically sound storytelling, emotionally charged heroism and a broader appeal to regional identity, it inherits the genre’s ideological limitations, reproducing communal binaries and selective historical memory.

In the post-Mandal period, dominant and populous castes such as the Marathas-Kunbis began to assert a more active role in shaping public debates on historical representation. Historically rooted in agriculture, the Kunbis are primarily small farmers and cultivators, while the Marathas came to be identified as a warrior-peasant caste. Over time, the boundaries between the two have blurred, mainly due to shared occupations, regional identities and political aspirations, leading to the often-used term “Maratha-Kunbi” to identify the collective. One of the largest and most influential social and political groups in Maharashtra, the Maratha-Kunbis were once central to the non-Brahmin movements that emerged after Phule in the early twentieth century and emerged as a dominant political force in Maharashtra by the 1930s. However, this did not lead to the triumph of radical, caste-conscious histories. Instead, socially conservative nationalist narratives continued to legitimise Maratha dominance while reinforcing conservative and anti-Muslim interpretations of their past.

Even though Marathi cinema has shown some responsiveness to the evolving discourse on Maratha history, it has yet to fully engage with the critical perspectives developed by Dalit and Bahujan activists, writers, publishers and intellectuals—such as Sharad Patil, founder of the Satyashodhak Marxist Party; M.M. Deshmukh, a prominent historian and activist linked with the Maratha Seva Sangh; and A.H. Salunkhe, a leading public intellectual—who have persistently contested the Brahminical interpretation of Maratha history. As have socio-political organisations such as the Sambhaji Brigade, a Maharashtra-based organisation that emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s and is particularly attentive to the nuances of the representation of the history of the Maratha-Kunbi community; and BAMCEF (Backward and Minority Communities Employees Federation), founded in 1978 by Kanshiram, the founder of the Bahujan Samaj Party. However, such critical perspectives remain largely absent from dominant narratives in mainstream Marathi cinema.

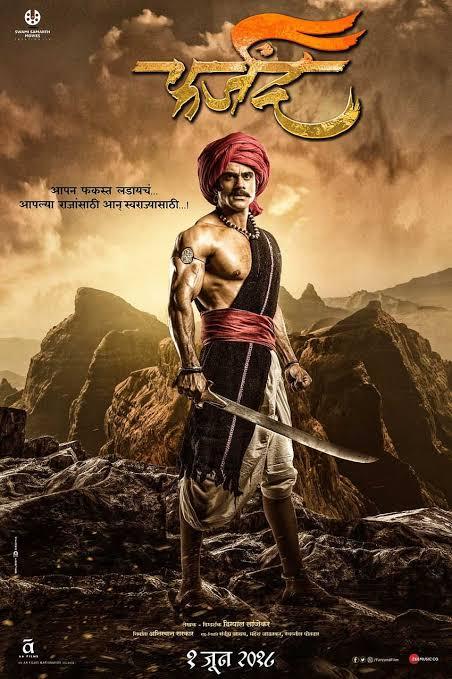

Farzand tells the story of a brilliant warrior from the Dhangar community, a rare focus in Marathi cinema, which seldom highlights non-Maratha figures apart from characters like Bahirji Naik. (Image courtesy of director Digpal Lanjekar.)

These films demonstrate greater visual sophistication and acknowledge the diversity of castes, for instance, historical dramas like Farzand (2018), Hirkani (2019) and Fattehshikast (2019) now foreground characters from diverse social backgrounds, such as the valorous milkmaid in Hirkani, and no longer emphasise Chhatrapati Shivaji as the protector of Brahmins (Go Brahmin Pratipalak). However, the ideological underpinnings, particularly regarding the representation of Muslims, have remained essentially unchanged and continue to be subtly embedded through depictions of villainous Muslim characters, partly in response to the growing influence of Hindutva politics in public discourse. The visual vocabulary of modern cinema still relies on stereotypical symbols such as green clothing, menacing expressions and religious chants to mark Muslims as the cultural “other.” For example, Farzand, a movie by Digpal Lanjekar that highlights the siege of the Panhala Fort by the Marathas, is based on the Maratha warrior Kondaji Farzand from the Dhangar community. The Adilshahi troops are visually marked with green banners and turbans, their dialogue includes references to “Kaafir (nonbeliever)” and their military campaign is framed as a religious crusade against the Marathas. The use of religious terminology and stereotypical visuals to depict the Adilshahi forces as fanatical invaders oversimplifies the conflict, ignoring the political and territorial motivations behind the siege. Farzand reflects Marathi cinema’s evolving complexity by including non-elite Maratha characters like the eponymous protagonist, yet it clings to socially conservative tropes and frames Muslim rulers as religious zealots with references to “jihad,” perpetuating the anti-Muslim sentiment prevalent in the genre’s history.

A significant reason for this disconnect lies in the lack of social diversity within the Marathi film industry itself. Most actors, directors, screenwriters and producers continue to come from specific social backgrounds and from particular locations like Pune and Mumbai. This demographic composition fosters a specific worldview, often shaped by cultural conservatism, caste privilege and an indifference to the realities of rural life, caste discrimination and inter-religious complexity. Accordingly, the Marathi cinema ecosystem has primarily remained distant to people from Dalit, Bahujan and Muslim backgrounds, whether as creators or as subjects. This homogeneity limits the potential of Marathi cinema to represent the fullness of Maharashtra’s social fabric. It keeps the ideological imagination tethered to a selective, often Brahmanical, memory of the past. Focusing on these socially conservative versions of the past neglects alternative perspectives that could offer a more inclusive, nuanced and critical understanding of history.

Chhaava illustrates both a continuity with and a partial departure from the established conventions of Marathi historical cinema. While the film refrains from overt ritualistic Brahmanical glorification, it remains ideologically tethered to earlier narrative patterns. It ultimately fails to transcend the entrenched anti-Muslim bias and its depiction of Aurangzeb and the Mughal forces remains starkly one-dimensional. Moreover, it is largely silent on the diversity within the Maratha kingdom under the leadership of Chhatrapati Shivaji and Chhatrapati Sambhaji, thus reinforcing a selective, Maratha-centric narrative, which was used mainly in the pre-1990s era.

In summary, the evolution of Marathi historical cinema—from the rigidly Brahmanical narratives of the early twentieth century to the more visually sophisticated yet ideologically familiar portrayals of recent decades—reflects an ongoing struggle over how the past is remembered and represented. While films made after the 1940s show notable advancements in cinematic technique and narrative form, the dominant worldview about Muslims has remained essentially unchanged. Chhaava follows this pattern as it amplifies the Hindu-Muslim binary. This selective remembrance reinforces a narrow cultural memory and exemplifies the paradox of contemporary Marathi historical cinema: while it has evolved in form and reach, its ideological framework remains constrained by selective memory, cultural conservatism and a reluctance to embrace social diversity fully.

Hirkani is a film about a courageous woman from the Maratha era, belonging to the Gavali (milkmaid) caste. Though Hirkani was a popular figure, only recently have films begun highlighting non-elite Maratha characters. (Image courtesy of director Prasad Oak.)

In case you missed the first part of the essay, you can read it here.

To learn more about films that evaluate the impact of the rise of Hindu nationalism in India, read Najrin Islam’s reflections on Natesh Hegde’s Pedro (2021) and Ankan Kazi’s essays on a curated selection of films by Vikalp that explore the increasing polarisation in Uttar Pradesh and on Kasturi Basu and Dwaipayan Banerjee’s A Bid for Bengal (2021).