Gulf ⇄ South Asia: Unveiling Stories of Migration

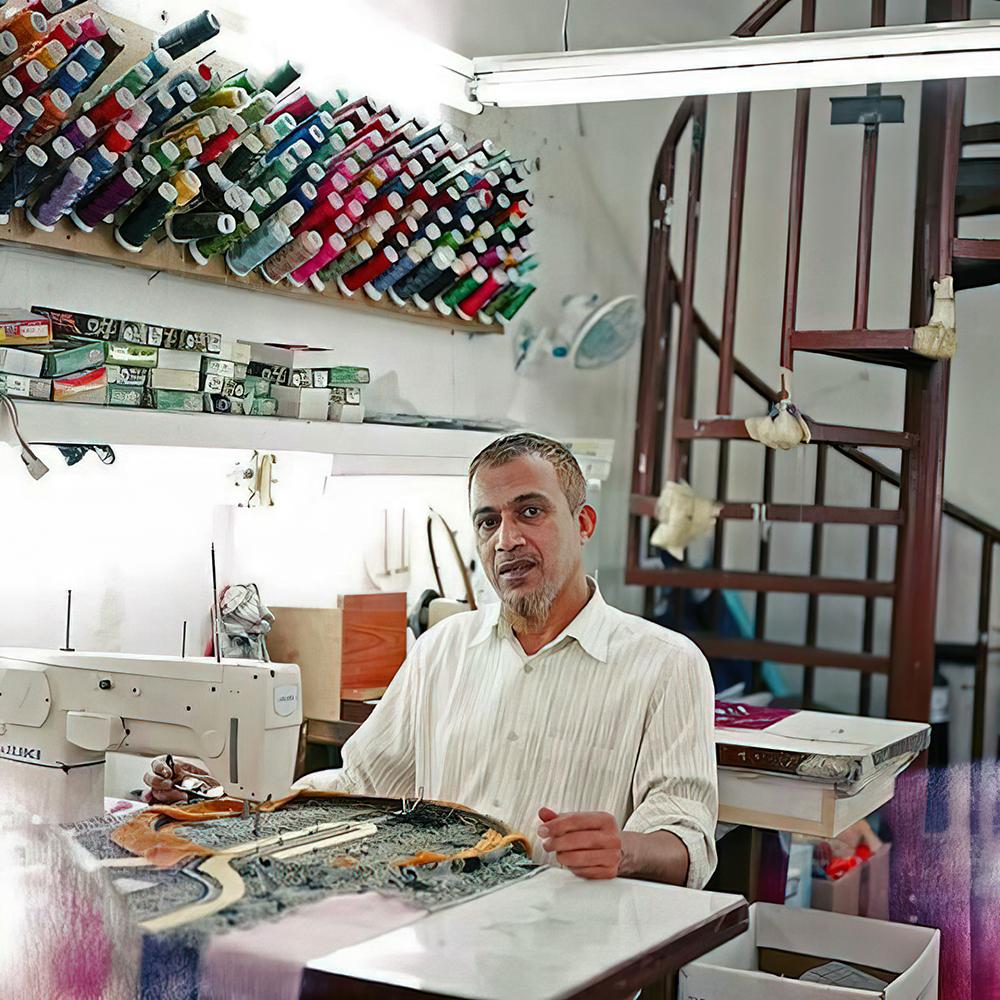

Ibrahim M. Yusuf Hafizi from Gujarat, who worked in the Bu Salem Tailoring Workshop in Deira, Dubai. (Photograph by Reem Falaknaz. Dubai, 2013. This Momentary.)

A colour photograph of a tailor from Gujarat working in Dubai, featured on the Instagram handle of Gulf ⇄ South Asia, is accompanied by an excerpt from an interview. Here, he states that he does not carry photographs of his children as it might tempt him to leave his job and return home. With more than 3,000 followers, Gulf ⇄ South Asia invites people to share such photographs and memories, connecting the Persian Gulf and South Asia in the twentieth and twenty-first-century.

South Asian communities have been migrating to the Gulf—comprising Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Oman and Kuwait—as manual workers for many centuries and especially after the oil boom of the 1970s. These communities constitute the largest expatriate population there—a total of 8.5 million—among which Indian nationals comprise the largest segment.

Inspired by the Indian Memory Project as well as numerous Arabic Instagram accounts about Gulf history, writer and Arabic translator Ayesha Saldanha started this compelling Instagram account in March 2019. Born in India and raised in the United Kingdom, her interest in the region grew after her own relatives—including her grandfather—recounted experiences of working in Muscat, Oman and Doha, Qatar. When she moved to Bahrain in 2001, she became further invested in this shared history of migration.

The theme of human migration has been extensively chronicled by global media and often shows its subjects as victims of suffering and displacement. As noted by author Tanya Sheehan in her edited volume Photography and Migration, images taken by migrants themselves hardly come to the limelight or make front-page news. This online archival initiative is challenging stereotypes of migration between the Gulf and South Asia by not only featuring South Asian migrants at work but also presenting everyday photographic practices that are often marginalised in the historiography of photography. Such scenes include a birthday party at a new McDonald’s in Riyadh, friends enjoying themselves at the beach, an outing to Wild Wadi water park in Dubai and a picture taken post a game of cricket. Thus, documenting the non-linear, fragmented yet lived narratives of the immigrant experience.

Bilal Hassan recounts the excitement of birthday parties celebrated at the newly opened McDonald’s in Riyadh. (Riyadh, 1990s. From the private collection of Bilal Hassan.)

The Instagram handle also chronicles experiences, such as this narrative by Priya DSouza providing autobiographical notes on growing up in Qatar during the 1970s: “I did not know I was Indian or that my family was Catholic until I moved to India when I was seven. Not once was I made to feel different from the others, and I did not know I was.” Her story unearths a sense of community and bonding that crosses barriers of religion and cultural ethos.

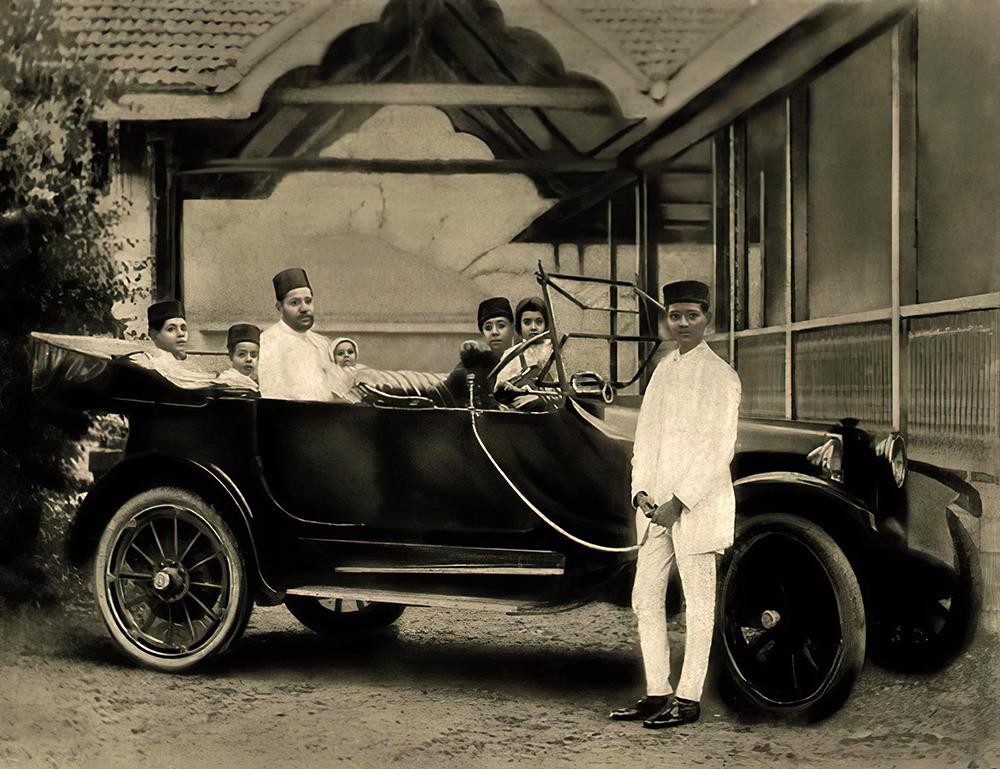

Along with tales of South Asian experience in the Gulf, Gulf ⇄ South Asia also brings to the fore interconnected histories like those of the Gulf Arabs in pre-Partition India. Many Khaleejis went to Mumbai to make money or get an education. A black-and-white image shows Muhammad Salem al-Sudairawi, one of the wealthiest Arabs in erstwhile Bombay, posing with his family at their summer home in Pune in 1918. His son, Fahad bin Muhammad al-Sudairawi, is credited with introducing football to Kuwait after their return in 1931, along with establishing the first Kuwaiti football team in 1932.

Muhammad Salem al-Sudairawi, his sons Fahad, Salem and Jasim, and his two young daughters Hessa and Sheikha seated in the family car, outside their summer home in Pune. The family’s Indian driver, Narayan stands next to them. (Pune, 1918. Sourced from kuwait-history.net, alayam.com.)

In addition to these stories, this Instagram handle also attempts to provide women agency by documenting the experiences of immigrant women—contesting systems of imperial and patriarchal power—which are often ignored in the archives. Exploring counterpublics, such initiatives offer possibilities of challenging this unilateral relationship by providing a platform to recover and restore independent voices. A story about a grandmother presents her odyssey from Mumbai to Qatar in order to join and support her husband, and speaks of her resilience.

Maria Piedade Bertha in her kitchen, baking a cake for her daughter Dagmar’s birthday. (Doha, 1979. From the private collection of Sheena Maria Piedade.)

All images from Gulf ⇄ South Asia.