Towards a Fugitive Photography: The Archives of Suresh Punjabi

In the book Artisan Camera: Studio Photography from Central India, Christopher Pinney recounts trudging through analogue materials in a godown which had been devastated by a storm. In this moment, Pinney was sifting through the debris for negatives and prints which had either escaped damage or could be salvaged. Such elemental wreckage notwithstanding, what he was devoted to recovering were the remnants of the accumulated archive of Suhag Studio. Founded by Suresh Punjabi in the late 1970s, Suhag Studio is located in the main street of Nagda Junction, a small town in Madhya Pradesh, India. A remarkable enterprise that has sustained itself through the past four decades and adapted in the shift from analogue to digital, it continues to operate in the present.

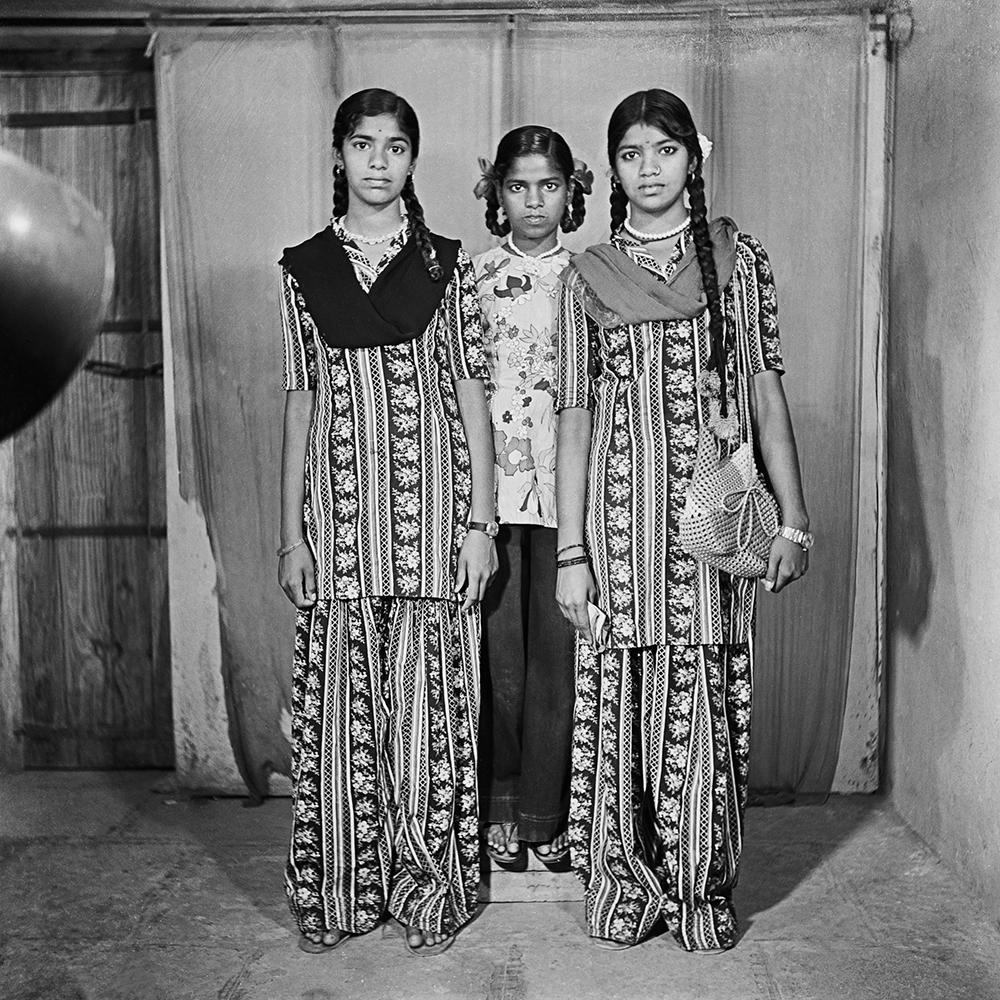

Untitled (Full-length Group Portrait of Three Girls). (Nagda, Madhya Pradesh, 1979. Print from Celluloid Negative. Image courtesy of MAP, Bengaluru.)

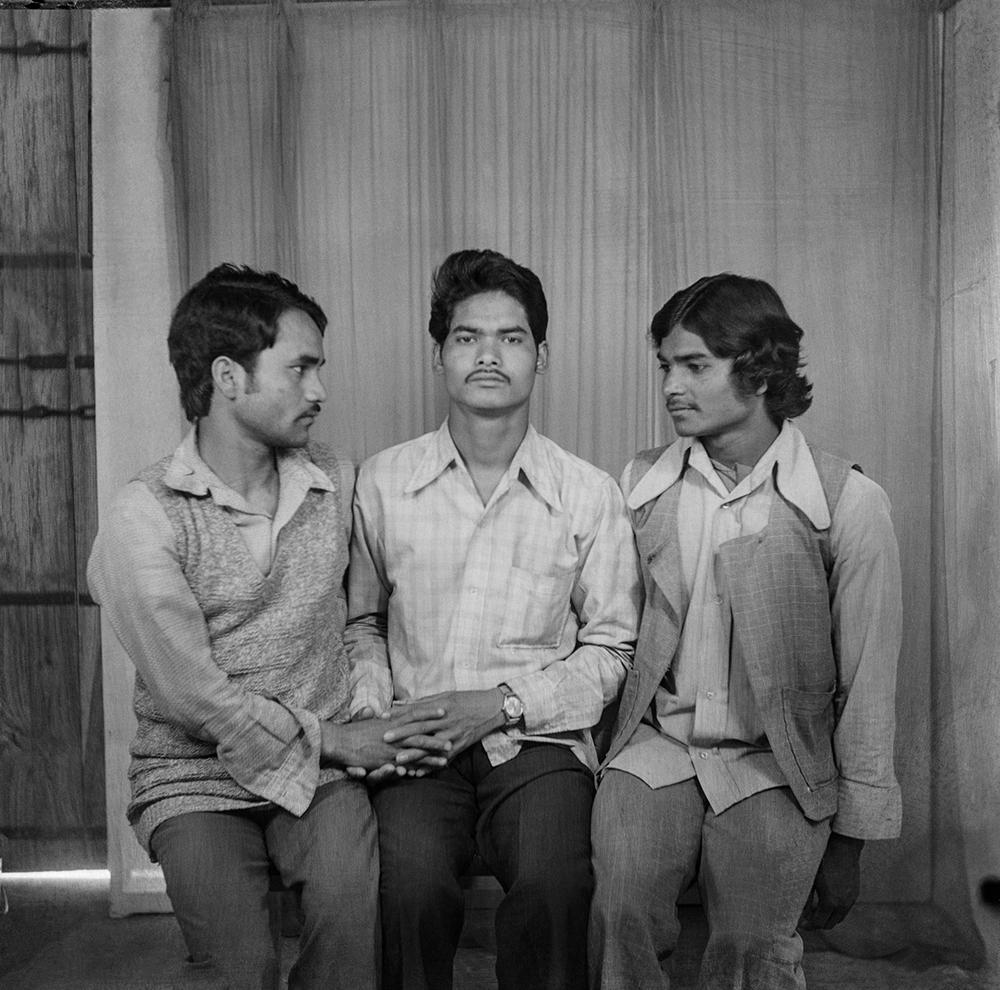

The Business of Dreams, an online exhibition curated by Nathaniel Gaskell and Varun Nayar at the Museum of Art and Photography (MAP), Bengaluru explores this collection. Presenting a selection of images from Punjabi’s archive, two threads of enquiry emerge in the exhibition: the ethnographic and the auteurist. The curators explore the interior lives and social denotations of those represented in the photographs, by reading the efforts that convey both the self-imaging of their present status and their projected aspirations. Compositions range from staged, fabulist performances to the standardised templates of identity documents. They are also keen to parse the stylistic impulse of Punjabi as a photographer, who conjures invention and deploys imagination within what Pinney describes as the “endlessly repeated space” of a 10 x 20 feet studio with a “…fixed repertoire of backdrops, props, lighting and framing techniques.” These two enquiries and their field, are not separated, but rather coalesce in the studio as a space for alchemical transfusions—where Punjabi’s imagery and symbols encounter and experience the imaginings of his customers, who could choose from an array of props. Collected by Punjabi, these included objects associated with economic status such as a telephone or a whiskey bottle (filled with coloured water).

Untitled (Portrait of a Woman with a Bunch of Grapes). (Nagda, Madhya Pradesh, 1981. Print from Celluloid Negative. Image courtesy of MAP, Bengaluru.)

Untitled (Full-length Portrait of Two Adolescent Bridegrooms). (Nagda, Madhya Pradesh, 1987. Print from Celluloid Negative. Image courtesy of MAP, Bengaluru.)

While the exhibition grazes the more “spectacle-drenched” images from the collection, giving due accordance to the trends, dispositions and accessories fashioned by Bollywood stars, as well as traditional accoutrements and textiles; it succeeds in highlighting a peculiar feature of the images which belong to the genre of identity photography. Intended as depictions of civic subjects drained of emotional propensities, Punjabi’s collection seems to challenge such readings with a vitality that emanates from the gaze and “attitude”—the classical term for figural deportment or pose in art as a vehicle of personality. By offering the viewer a series of identity photographs first, Gaskell and Nayar draw our attention to the power of gaze and the oblique traces of subjectivity. They propose the presence of a vocabulary in Punjabi’s collection which troubles the material constituents of a bureaucratic document, while adhering to the dominant schemata of such images. Tina M. Campt terms this practice of embroiling radical, personal frequencies within homogenous formats as “fugitivity." Such fugitive frequencies seep into the images which were meant to render legibility and function as documentary appendages in the civic processes of public institutions.

Untitled (Administrative Portrait). (Nagda, Madhya Pradesh, 1983. Print from Celluloid Negative. Image courtesy of MAP, Bengaluru.)

The exhibition also includes a small group of photographs taken by Punjabi at a wedding. A departure from the interior of the studio space, this also asserts the celebration of the marital bond implicit in their name. “Suhag” or marital bliss, affirms the position of the studio as a place which records and ensures, through the photographic medium, the maintenance of a social order predicated on kinship. Gaskell and Nayar explore Punjabi’s practice beyond the studio in a section titled, “Outside the Studio,” depicting scenes from weddings and raffles. Nayar notes the importance of these images in linking the studio to its socio-cultural context, and embedding a diverse and differentiated network of studio practice across regions. In an email conversation, Nayar explains:

“The idea of 'Nagda as one of many Indias' expresses our interest in the situatedness of Suresh's work, and the sheer multiplicity of other, equally situated studio practices it implies. Engaging with such archives today demands that we pay closer attention to regional contexts, and Suresh's act of 'stepping out' from his studio and into Nagda's everyday is consequential in this regard. It reminds us of a defining aspect of the medium, especially seen through his eyes: that, above all, photography is a social practice.”

Untitled (A Seated Portrait of Three Friends). (Nagda, Madhya Pradesh, 1979. Print from Celluloid Negative. Image courtesy of MAP, Bengaluru.)

All images by Suresh Punjabi, Suhag Studio.