Erasing the Past: Photography in the Archive and the Work of Imran Channa

Imran Channa’s works span different media, from installation, digital moving images to drawing and painting, with the historical narrative as the central locus. From Memory series (2015).

After receiving his training in fine arts at the National College of Arts, Lahore, in 2004, Imran Channa has practiced a multi-disciplinary work ethic that investigates the various ways in which medium and translation affect our understanding of the complex histories of modern South Asia. Working with photography, graphite drawings and painstaking methods of erasure, his works foreground the complications of reading historical archives, whether in relation to colonial methods of aesthetic description or modern events like the Partition. The photograph (and methods of photography) emerges as the name for an itinerant practice, as Zahid R. Chaudhary puts it, which cannot be fixed into any innocent claims for autonomy or truth. In this way, Channa’s work interrogates the nature of photography and its claim as a medium, especially a transparent one, which can communicate perfect historical knowledge to the present. They become instead, in the words of Chaudhary, “forms of transmission”, so that the drama of their temporal disjunction (from the moment when the photograph was taken to when it is being perused) assumes a mode of critical and creative thinking for the modern citizens of South Asia to create their own presence within those archives.

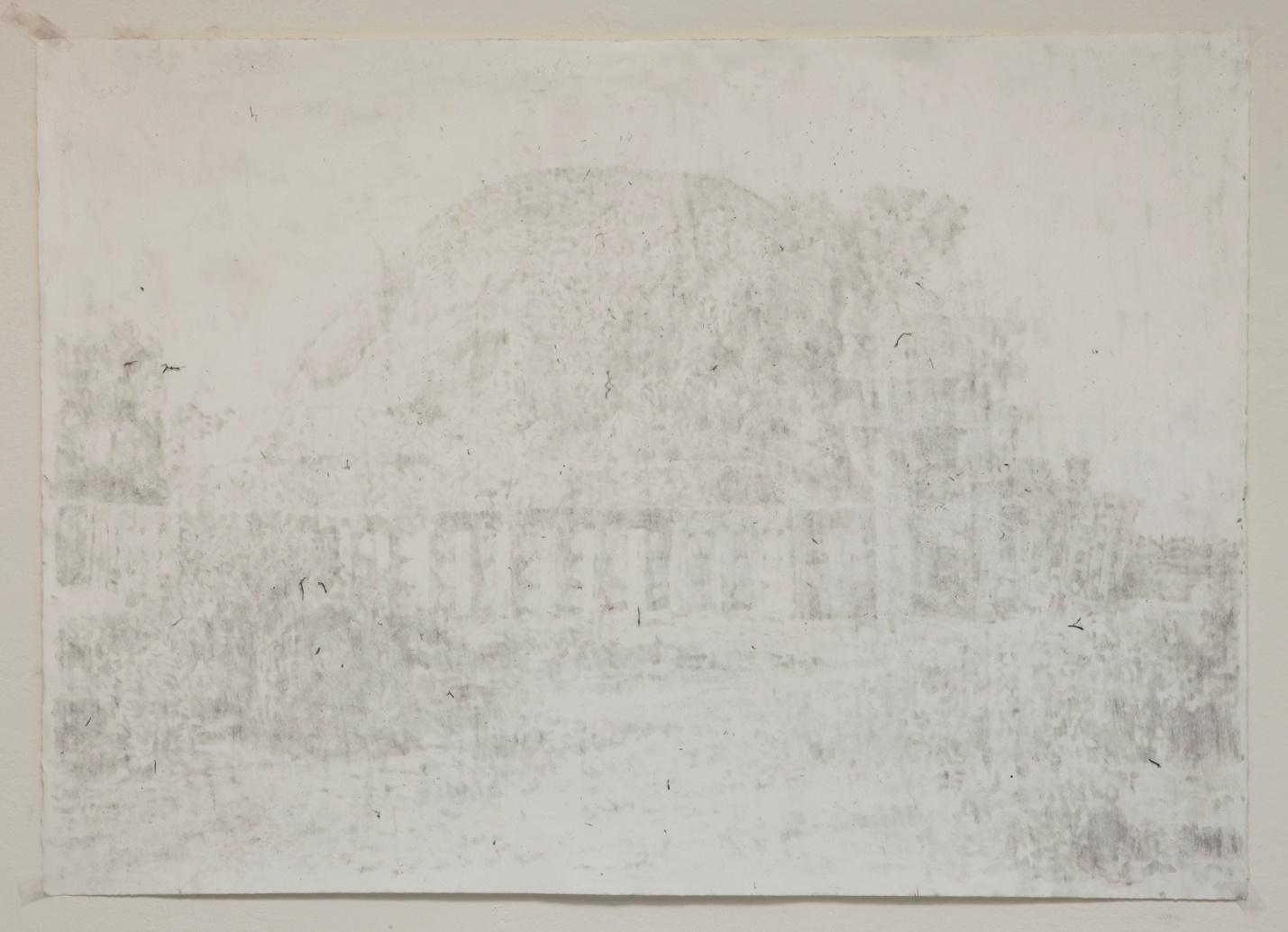

Channa uses colonial photographs like these and performs a creative act of erasure to foreground their aesthetic reliance on imperial modes of control and total archival visibility.

Channa’s re-treated, erased and variously reconstructed works are in conversation with past masters—whether it is colonial photographers like Linnaeus Tripe or modern ones like Margaret Bourke-White, who shot some of the most well-known photographs of the Partition for LIFE magazine. The role of the photograph changes with the context of its publication or exhibition. Tripe’s photographs now tend to represent an affective and romantic history of architecture as photography, capitalising on and dramatising the very stillness of such structures. Bourke-White’s images, on the other hand, represent a history of exclusion since her images were not available for critique or reflection to the traumatised subjects she photographed during the Partition.

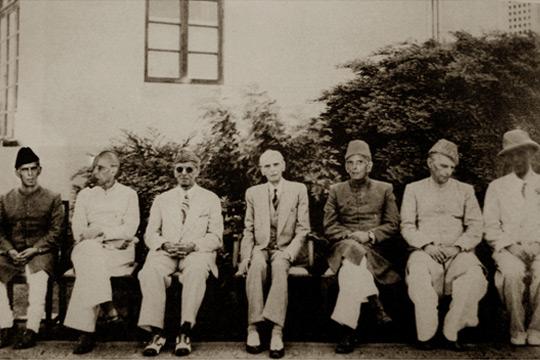

From Find the Real Jinnah (2008), where Channa replicates several images of Muhammad Ali Jinnah in a single image, mirroring photographs in which state officials would often sit and pose in front of a camera.

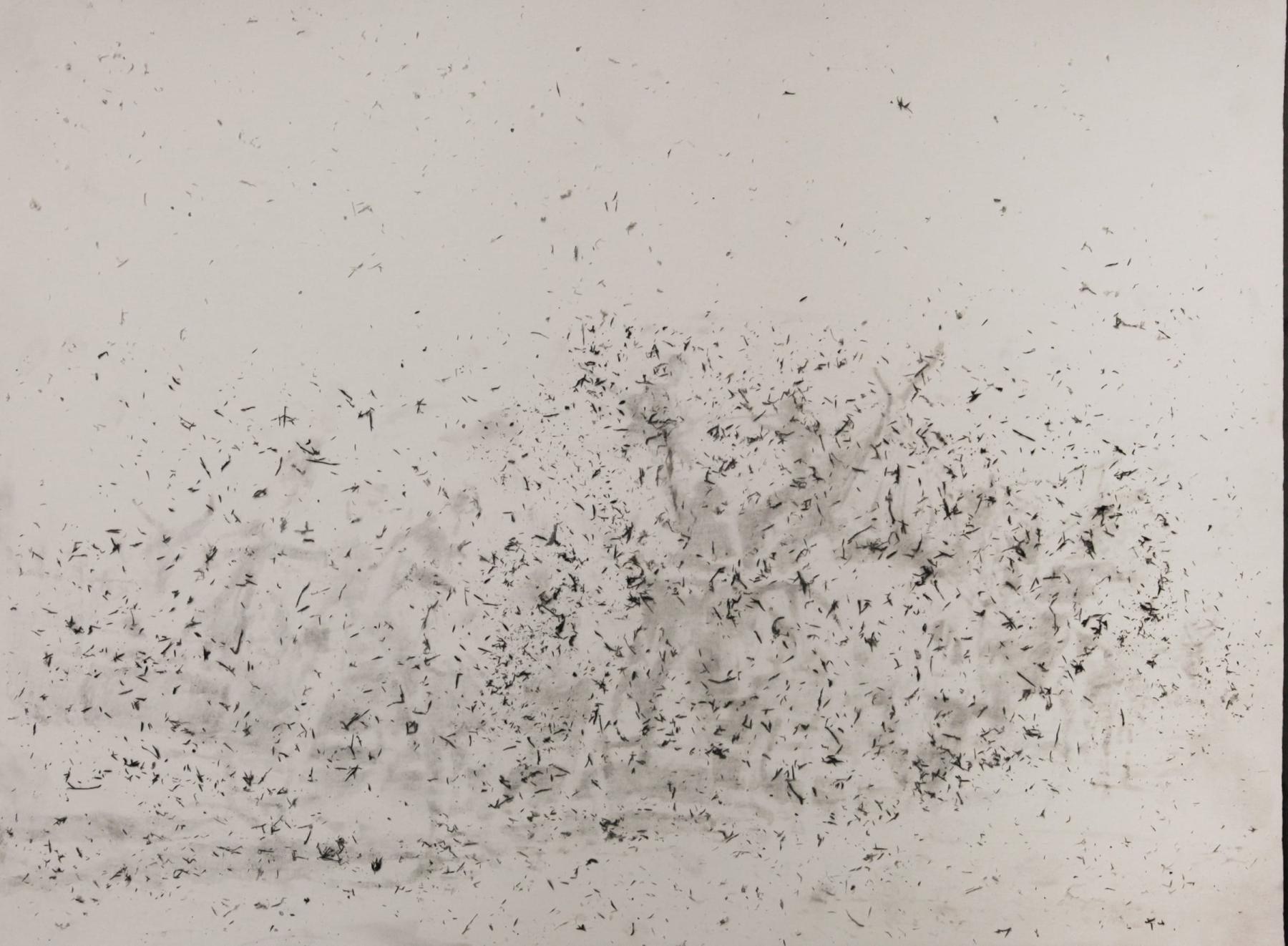

A laborious, bodily investment is made in Channa’s method, as if to introduce a sensual movement into the intellectual system of producing South Asian historiography itself. As Iftikhar Dadi describes it while writing about the artist’s Enclosure/ Erasure series:

“His process in all three series involves first producing large-scale drawings using a dark pencil such as a 9B, to create an enlarged realist image faithfully based upon the archival photograph. After the drawing has been completed, Channa practices a laborious process of erasure and re-inscription, effacing the legibility of the original image. This process of erasure is extremely arduous. It involves a very considerable effort, and is physically painful on the muscles and fingers of the artist. This sense of bodily involvement, pain, and fatigue, as Channa reworks and erases the photographic image, creates an embodied act of creative destruction leading to a kind of new inscription, which insists on the necessity of the substrate image even as it seeks to question its veracity and its positivist transparency.”

Marks of erasure, preserved carefully in Channa’s practice, allow us to pose a different set of detritus— matter or remainder—that can point towards a new narrative of past images and their claims towards wholeness.

Installation view and stills from Lik Likoti 2 (2013), where Channa distorts scenes from the Star Wars films.

While historical trauma can hardly be recreated down to its last, original detail, the methods adopted by Channa seek to communicate trauma through such acts of bodily endurance and physical pain. It does little to “clarify” or make any of the difficult subjects he deals with any easier to understand. In fact, it introduces a regime of controlled opacities and obscurities that are meant to evade the categories by which these histories are made familiar to the competing nationalisms of postcolonial states like India and Pakistan. The tension between abstraction and realism, as Dadi picks up on, is one between the conceptual swerves of history-writing and the material detritus that can either support it or undo its purposeful work; it is also suspended between the violence of those conceptual structures and the material presence of traumatised bodies. Channa’s works deal with these difficult histories by getting under the skin of the archive, re-animating it for creative acts of truth-telling that can attend to the narrative constructions of the past while speaking to the realities of our vexed present.

Installation view of Holy Water (2018), consisting of water collected from rivers Jordan (Israel), Ganges, (India), and the Well of Zamzam (Saudi Arabia).

To learn more about contemporary artists who seek to make critical interventions in colonial histories through their practice, revisit Arushi Vats’ reflection on Bakirathi Mani’s reading of Seher Shah’s work and Najrin Islam’s conversation with Renluka Maharaj. To read more about the National College of Arts, Lahore, revisit Ankan Kazi’s essay, in which he traces the institution’s early history.

All works by Imran Channa. Images courtesy of the artist and Kang Contemporary.