Reconsiderations of the Popular: In Conversation with Iftikhar Dadi

The intergenerational show Pop South Asia: Artistic Explorations in the Popular, co-presented by the Sharjah Art Foundation and the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA) in Delhi, sought new as well as iconic discoveries of modern and contemporary art across South Asia. The project brought together post-independence works focusing on self-representation and hybrid forms, seeking non-mainstream, para-institutional/non-academic means to articulate our contemporary socio-cultural and political moment.

Emerging from colonial rule in the 1950s, newly independent nation-states across South Asia sought revisionist political and aesthetic genealogies. Artists incorporated street culture, new forms of journalism, folk art, montage, moving images and even subversive press to create a language in art that generated inter-relations between images created by and related to the anonymous, outsider, activist and citizen. Re-imagining stereotypes within the South Asian context led to a dynamic new brand of art-making, contesting established principles dictated by the “documentary” mode. Pop art emerged as a fresh language—a resistance to academic realism and colonial history—and can now be read within a broader decolonial perspective.

.jpg)

Exhibition view, Pop South Asia: Artistic Explorations in the Popular at KNMA Saket. Image courtesy: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art.

In this interview, Prof. Iftikhar Dadi reflects on popular arts practices, similar to how they developed in other zones of the Global South, the Middle East and even South Africa, to which South Asia is intricately connected.

Rahaab Allana (RA): Thinking about “boundary” and “spatiality”, one of the notions that struck me while viewing Pop South Asia was the challenge of confronting the “idea” of South Asia as one tries to articulate thematic or narrative trajectories around visual culture and image practice in the region as a whole. In that context, I was interested to know how you began the initiative. How did considerations of the “vernacular” inform your understanding of what popular culture is in the present?

Iftikhar Dadi (ID): The exhibition was guided by Amrita Jhaveri in its early stages. In time, the KNMA came on board with Roobina Karode as the co-curator. But my own artwork with Elizabeth (Dadi) also straddles this terrain—creative and locally-inspired aspects of pop art from the region.

For instance, when I first started working as an artist, Karachi as a city had only a few galleries. So, the formal art world was quite small, but the place itself was full of vibrancy. It led me to think about what elements of the popular we were missing in terms of our thinking about creativity and visual practices developing in mega cities.

The initial impetus was to question what “pop” is—beyond Western cultures of reference emerging from New York, such as through the work of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. And to think beyond European terms as well—beyond the capitalist realists in Germany or independent groups in London. There was an interesting book edited by Kobena Mercer called Pop Art and Vernacular Cultures (The MIT Press, 2007) that was very influential, especially Geeta Kapur’s essay on Bhupen Khakhar in that volume.

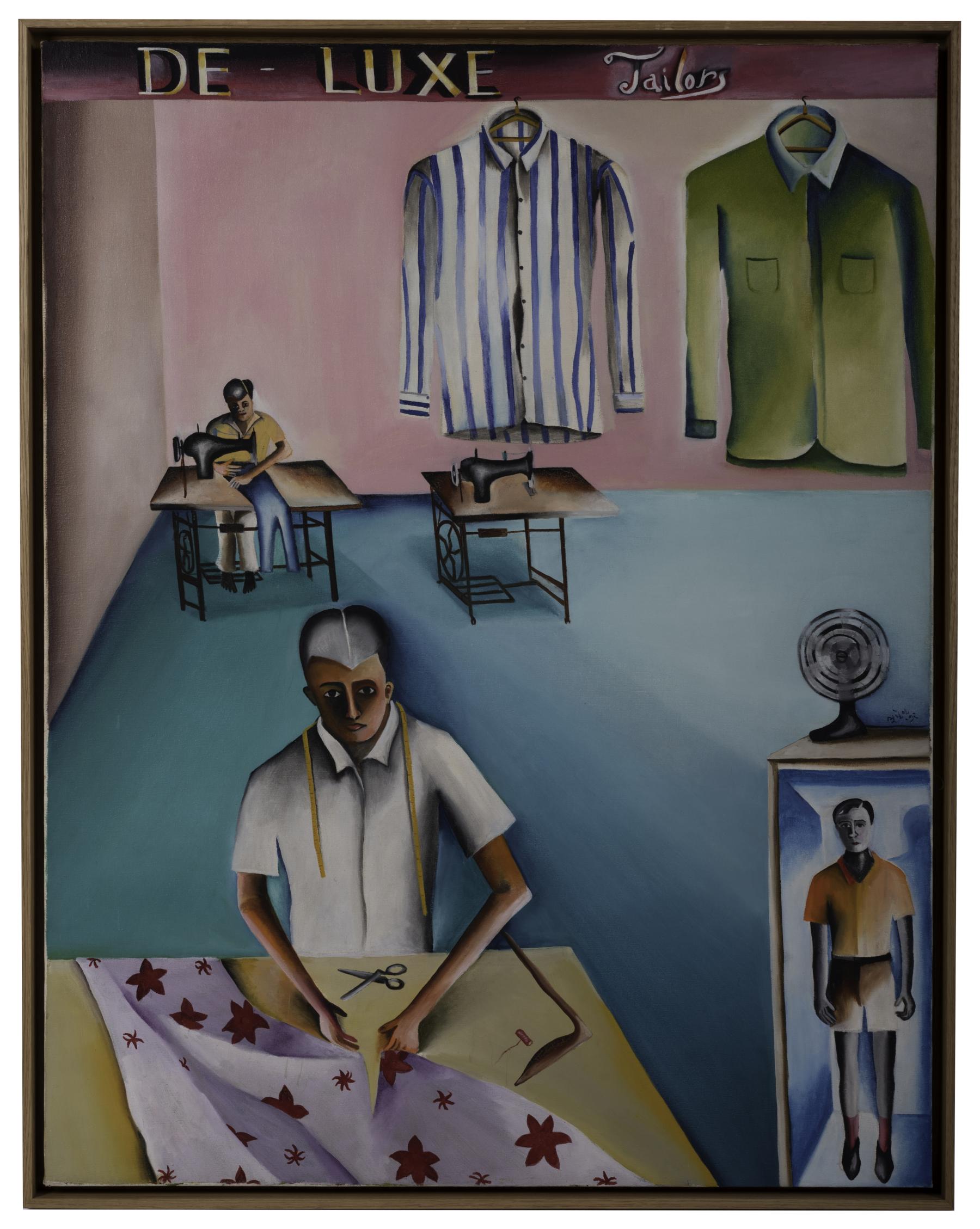

Bhupen Khakhar, De-Luxe Tailor, 1972, Oil on canvas, Collection: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art.

In 2015–16, there were many exhibitions related to this subject—Global Pop and another one named The World Goes Pop (Tate Modern, 17 September 2015–24 January 2016). There was a growing realisation that pop had to be thought of in international terms and these shows expanded the orbit to Japan, Latin America and Eastern Europe. But they did not really look at Africa, the Arab world, South Asia or even Southeast Asia. There was only one film from the subcontinent that was shown, called Abid (1972) by Pramod Pati.

There have been other smaller shows like Kitsch Kitsch Hota Hai: Kitsch and the Contemporary Imagination, organised by Gallery Espace (India Habitat Centre, New Delhi, 2001). However, in Pop South Asia, we were trying to avoid value judgements, by surpassing words like “kitsch”, which imply a certain kind of discrimination in the sense of being camp or relating it to a particular canon/genre, or in fact to popular aesthetics as it seeks to define good and/or bad taste.

We wanted to avoid singular associations with Western pop or merely thinking about advanced capitalism in terms of the commodity image and media culture around it. Secondly, in our show, we have included several sub-themes so as to surmount the domination of geographic considerations. Hence, we did not want to organise the show with pop from metropolitan centres like Mumbai or Dhaka alone. The other concern was how to think about pop art intergenerationally. If you go in the first gallery, you find the prints of Ravi Varma's; in another, there is a dialogue across his prints with works by Atul Dodiya and Pushpamala N., and further on with Tejal Shah. There is also a dialogue with Maligawage Sarlis, who was an academic painter working on Buddhist themes and making prints in the 1930s. He is not really well known. And so there is a retake on tradition. The second theme was bazaar capitalism and print culture; the third was cinema and media; the fourth was borders and protest; the fifth, modernity in urbanism; and another was self and identity.

Installation View | Pop South Asia: Artistic Explorations in the Popular | KNMA Saket | 9 February – 30 April 2023.

RA: The exhibition is framed inter-regionally and I noticed how it addressed the idea of protest through the prints of Lala Rukh, for instance. It reflects the relationship with DIY subversive print cultures that India had, especially in the 1960s and 1970s, such as in the magazine Vrishchik (1969) or Arvind Krishna Mehrotra’s Damn You (1967). Hence, I feel that the show expands the general descriptor of “pop culture”, especially when one sees inflections of the urban in Seher Shah’s work, which is not quintessentially pop art. I wanted to ask you a little bit about describing the word in new ways in today’s context as our idea of the popular becomes dynamic with the coming of digital culture. How do you position the “popular” in an era of simulacra and hyperrealism?

ID: To begin with, Rukh actually had alliances with feminist movements in Bangladesh and India. One of the prints in this exhibition was actually developed in Bangladesh by a women's collective and later printed in Lahore as well.

Of course, the digital era changes things because the means of production are in the hands of practically everyone. The second aspect is real-time communication exchange and the almost costless ways of circulating and multiplying the flow and spread of imagery. In this respect, photography and video enormously expand what and where the popular is and can be located today. If there is some specificity to the age of the digital and to internet 2.0, the questions that pop art asks us are related to simulacrum, which is about the lack of the original and about the recourse to everyday imagery, right? I think these are relevant questions to ask of digital media as well. So, in terms of this intergenerational dialogue, we have works from the 1960s by Khakhar, and from the 1970s–80s by K.G. Subramanyan, as well as Mian Ijaz ul Hassan and so on. We did not stress the digital era too much, though there are two video works by Abdul Halik Azeez from Sri Lanka, in which he thinks about living in the city and a kind of phenomenological immersion with the sensory bombardment of everyday life.

Exhibition view, Pop South Asia: Artistic Explorations in the Popular at KNMA Saket. Image courtesy: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art.

There were some other works we wanted but could not get because there was a lot of profane language [in them]. This show is not meant to be comprehensive or definitive, but is meant to open up other questions—for instance, is the popular associated with the right wing, with the rise of “WhatsApp University”, and is it necessarily something to be celebrated then? One of the guiding principles for this show is that we did not wish to look at the popular directly but through self-conscious artists, artistic practices and their engagement with the popular. If we look at the popular as a whole, it is much too big for us. So, we looked from the vantage point of an artist—to imbibe the kind of sensory or conceptual reflexivity and criticality they bring to relationships in an urgent manner.

Installation View | Pop South Asia: Artistic Explorations in the Popular | KNMA Saket | 9 February – 30 April 2023.

To read more about Iftikhar Dadi’s scholarly work on politics and popular culture, revisit Ankan Kazi’s reading of political posters in Pakistan. To read more about some of the events organised in conjunction with Pop South Asia at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, read Mallika Visvanathan’s reflection on the symposium Imaging South Asia.