Bollywood’s Tryst with Orchestra Music: The Instruments of Disco in the 1980s

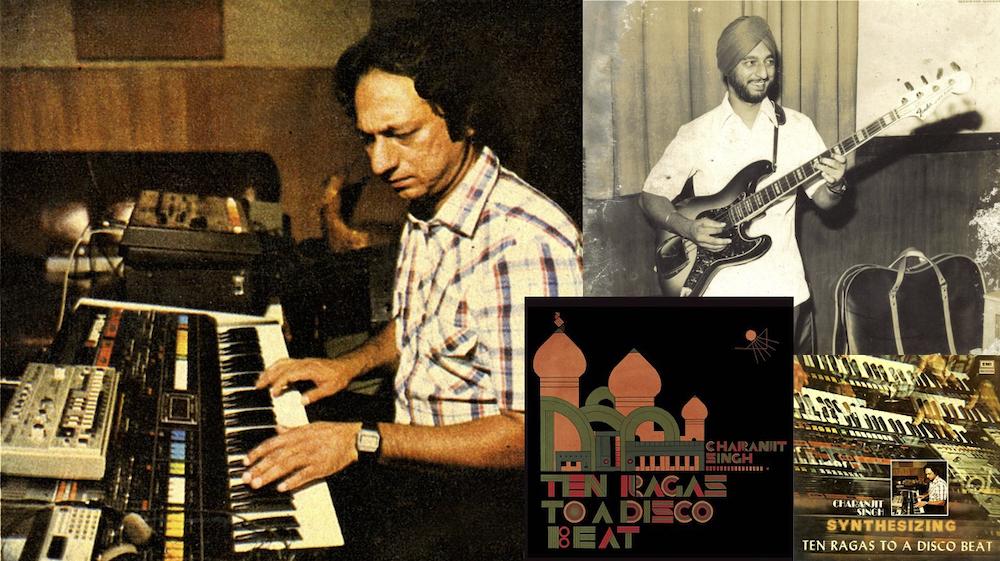

Charanjit Singh, a session musician and an arranger for music director R. D. Burman is belatedly credited to have inadvertently invented acid house—a sub-genre of house music that was developed in the 1980s—with his 1982 album, Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat, considered a commercial failure. Just like Singh’s tinkering and remixing of the Indic resulting in the chance invention of acid house, South Asia’s tryst with disco was a cannibal experience—chomped off and pilfered from here and there.

Charanjit Singh was a session musician and arranger for music composer R.D. Burman. Image courtesy of Dazed Digital.

Journalist and critic Geeta Dayal suggests that disco music was very much part of the zeitgeist in the 1980s, with Bollywood film soundtracks chock-a-block with such songs. The ephemeral “disco moment” in Hindi cinema of the 1980s might seem to be one of the embarrassing practices, with its pilfered tunes and aesthetic citations (one that fades out with the coming of satellite television and channels like MTV). While it is hard to own up to those practices in the present regardless of how deeply involved one may have been in the past, it also opens up forgotten histories of archiving, collecting and listening. In the first of this two-part post, I attempt to parse out the nature of the disco revolution in Hindi film music.

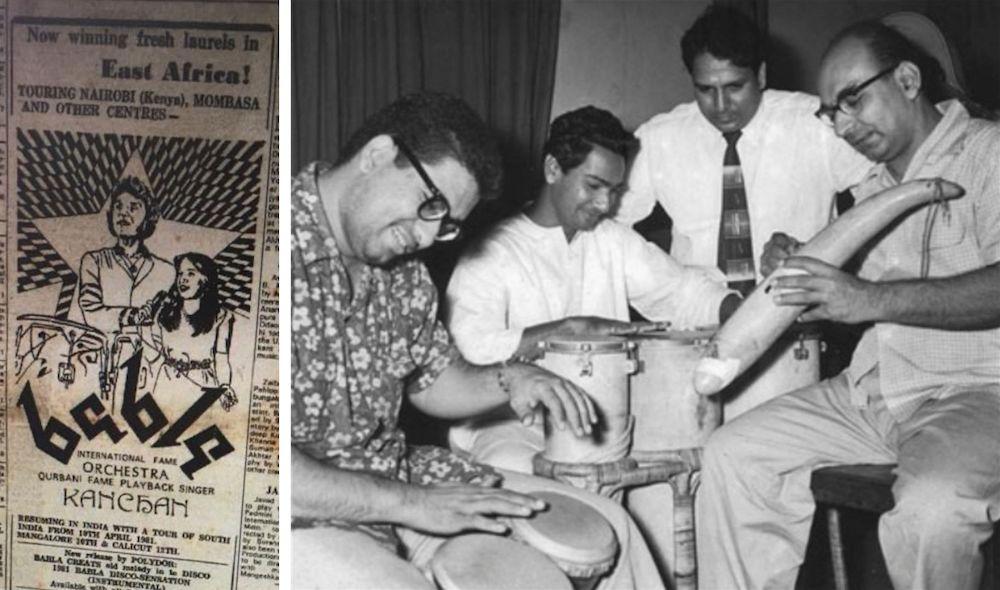

In my extended conversation with Raju Singh, Charanjit Singh’s son, in 2018, I realised that by the early 1980s, music composers in Hindi cinema had acquired a few prominent electronic musical instruments. The disco-era Bombay film songs were often composed and arranged to then exotic instruments, usually procured by the musicians themselves on their tours abroad. Film musician Kalyanji Virji Shah had imported a clavioline (an electronic keyboard instrument) from London in as early as 1954 and recreated the Been music of the film Nagin (Rajkumar Kohli, 1976) on it. His brother, Babla Shah, had a huge following in Trinidad in the 1980s for his chutney disco. Babla and his wife Kanchan, under their banner Babla Orchestra, conceived Disco Garba and Disco Dandiya by fusing a folk idiom with disco beats. On one of his tours to the United States of America, Babla brought back Rototom drums to create the percussion track for the song “Laila Mein Laila,” sung by Kanchan in Feroz Khan’s Qurbani (1980). Babla offered to compose the soundtrack in Bombay when Feroz Khan was ready to get the music recorded in London.

An advertisement for Babla Orchestra's international music tour in the March 1981 edition of Screen magazine (left). Image courtesy of National Film Archive of India. (Right) Music arranger Kersi Lord, far left on the bongos. Image courtesy of Gregory D. Booth, Behind the Curtain: Making Music in Mumbai’s Film Studios (New York: OUP), 2008.

Raju Singh informed me that Charanjit Singh was in possession of the only vocoder in the industry (an analog forerunner of the auto-tuning gear of today). It was used to produce the “robotic voice” of Kishore Kumar rumbling in his deep baritone “paisa” in song “Paisa Yeh Paisa” in Karz (Subhash Ghai, 1980). Similarly, his transicord, an electronic accordion, was famously used in R.D. Burman’s composition “Dil Lena Khel Hai Dildar Ka” in Zamane Ko Dikhana Hai (Nasir Hussain, 1981). For this song, Singh had used his left hand to provide the bass on the guitar and played the transicord with his right hand, a brilliant mastery of balance, show of strength and musculature of torso and hands. In a similar fashion, Singh had further introduced his Technics keyboard (which was till then only used in live shows) for “Tu Roothe Toh Mai Ro Dungi” from the movie Jawaani (Ramesh Behl, 1984). In the next few years, Singh and other arrangers who worked with R.D. Burman, such as Kersi Lord, started combining several electronic synthesisers and drum machines like the iconic Roland TB 303, TR 808 and Jupiter 8. The combination of the three created the acid house style.

A screengrab from Disco Dancer, featuring actor Mithun Chakraborty. (Babbar Subhash. India. 1982. 134 minutes.)

A unique sensibility of the Hindi filmi disco comes from its special affinity to orchestra and the brass band. In Brass Baaja: Stories from the World of Indian Wedding Bands (2017), anthropologist Gregory D. Booth writes about its association with north Indian weddings and how these urban musical bodies fuse folk sensibility with film music that is disseminated through radio, film, and cassette culture. Some of the media objects that create the sensory infrastructure of orchestra demonstrate South Asia’s history of chance encounters with residual technology from the west. These include Albert system clarinets, trumpets, baritone horns, and percussion (snare, tenor and bass drums), tenor and alto saxophones, valve-trombones, cymbals and sousaphones, along with battery-driven sound systems which enable microphone-wielding singers, and the Casio, an electronic keyboard that goes by the name of its most popular brand. This is perhaps the reason why Bappi Lahiri-Vijay Benedict’s cult filmi disco song, “I am a Disco Dancer,” (1982) positions DISCO as an acronym for this unique socio-musical sensibility composed of dance, item, singer, chorus and, finally, orchestra.

To read more about the disco revolution in Hindi film music, please click here.