Moving Past the Feeling: Nostalgia for the Future and Lovely Villa

I begin with the story of two buildings, or the story of my entanglement with them.

Living in New Delhi, I have often felt that I am moving from the shadow of one modernism to the next. How to eat kebabs at Rajinder Da Dhaba without looking at the A. P. Kanvinde-designed National Dairy Development Board building (NDDB)? The circuitous climb to the right bureaucratic table where your work might get done feels much like the ascendant rise of concrete in the New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC) building designed by Kuldip Singh. The forms of these buildings radiate a weak light, the afterglow of certain visions of the future linger in the air. These are ordered enclaves of walls and columns, landscaped gardens and signages, but the life which animates them spins irreverently to other tunes.

In the shade of the first building stands a juice stall and a florist. A tea-seller sits between these and you’re likely to find several autos parked at this corner. The National Cooperative Development Corporation (NCDC) office—infamously monikered the “pyjama” building—was designed by Kuldip Singh, with engineering by Mahendra Raj. Rising as delicately as a stack of Jenga blocks, it comprises two textured, concrete-clad towers that progress in large slab-like floors, tapering upwards in a zig-zag fashion to meet at the top. The corner is a place to spot the people who work in the building. Figures move through its crossed staircases, or people talk on the phone in the small, open corridors connecting the two towers. These everyday figures appear almost cinematic when seen from the ground, framed by the decisive, angular lines of the building—a sight that has always stayed with me. I think of them when I read Andreas Huyssen describe the genre of the metropolitan miniature as “a paradigmatic modernist form that sought to capture the fleeting and fragmentary experiences of metropolitan life, emphasising both their transitory variety and their simultaneous ossification”. Taking the term “miniature” from Walter Benjamin’s description of the arcade as “a world in miniature,” Huyssen describes modern metropolises as “laboratories of perception”. To reproduce a specific vision of the world in miniature is one way to describe the housing project which is at the centre of the documentary Lovely Villa: Architecture as Autobiography (2019).

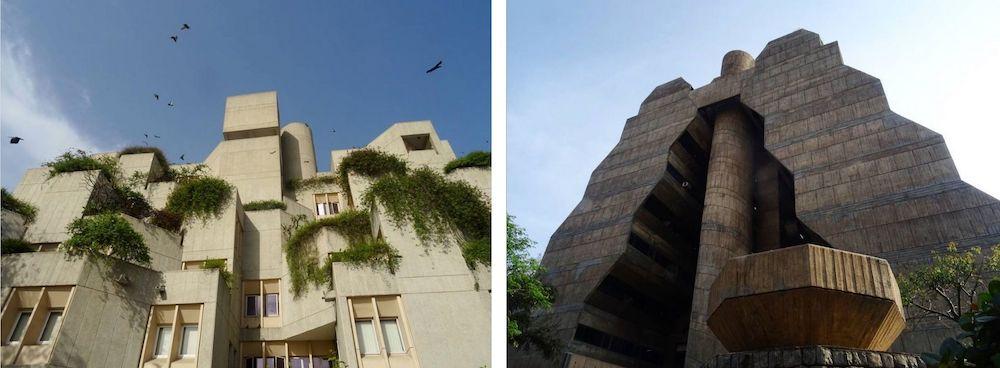

Left: The headquarters of the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) in Safdarjung Enclave designed by A.P. Kanvinde. Right: The National Cooperative Development Council (NCDC) building on Siri Fort Road designed by Kuldip Singh. Both photographs by Mila Samdub. New Delhi, 2017. (Images courtesy of @DelhiModernism, Instagram.)

Lovely Villa—directed by Avijit Mukul Kishore and Rohan Shivkumar—studies a family and the housing society it inhabits, built under the ‘Own Your Home’ scheme in the 1970s by the Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC). The Jeevan Bima Nagar in Mumbai’s Borivali West, also known as the LIC Colony, was designed by Charles Correa. The defining architectural features of Jeevan Bima Nagar buildings are also perhaps some of Correa’s most iconic. A vertical sweep of step-like terraces descending into gardens and opening at each level a little more to the sky and tree cover; windows allowing for cross-ventilation; wooden doors and oxide flooring, to name a few. The Jeevan Bima Nagar buildings in Bengaluru, also designed by Correa in the 1970s, are close cousins of these apartments in design.

Apartment blocks in the LIC Colony in Borivali, Mumbai, designed by Charles Correa. (Images courtesy of Charles Correa Foundation.)

There are finer details revealing what American critic Ben Lerner describes as “the texture of et cetera itself” in his novel Leaving the Atocha Station (2011)—elements so quotidian, they nearly miss the eye. Incongruous platforms raised at the entrance to the home and balcony create a place to sit that is “in-between” the inside and outside. There are half-doors leading to the kitchen, revealing presence and concealing activity. Small counters are carved into walls through which utensils can be passed to eager hands. To live in a place designed by Correa is to be caught in a game of hide-and-seek, each part of the house considering what it shows or covers for its inhabitants. A family, though a unit, is not just a sum of its parts—each coin collects, collides and disperses into discrete corners of the carrom board at the flick of the architect’s invisible hand. The hand of the state, however, is not only welfarist but also reformist. It seeks to bring together members across classes and communities in a blind allotment system, reinforced by the architect’s plan for houses of differing sizes and layouts within the same building.

Stills from Lovely Villa. (Avijit Mukul Kishore and Rohan Shivkumar. India. 2019. 32 minutes. Images courtesy of the artists.)

Lovely Villa is infatuated with Correa’s style and makes no attempts to hide this. The opening is overlaid with the meditative notes of raga Malkauns in Padmavati Shaligram’s unforgettable voice and shots of fallen amaltas or trees blooming with gulmohar. The lens grows sentimental with the arrival of filmmaker Rohan Shivkumar’s family—the housing project is now a home, a troop of two led by a couple with scientific temperaments. We’re shown the ways in which everyday life occurs in the house. Someone paces the length of the balcony while talking on the phone; later, a group of friends pose for dramatic portraits to be shared on social media with coloured clouds hissing from a handheld gas sparkler. A single wall of the home is traced across time. Painted grey, then blue—mirth and frivolity, aging and disrepair play out against this solid backdrop. The buildings may appear rundown but life persists and even thrives in them.

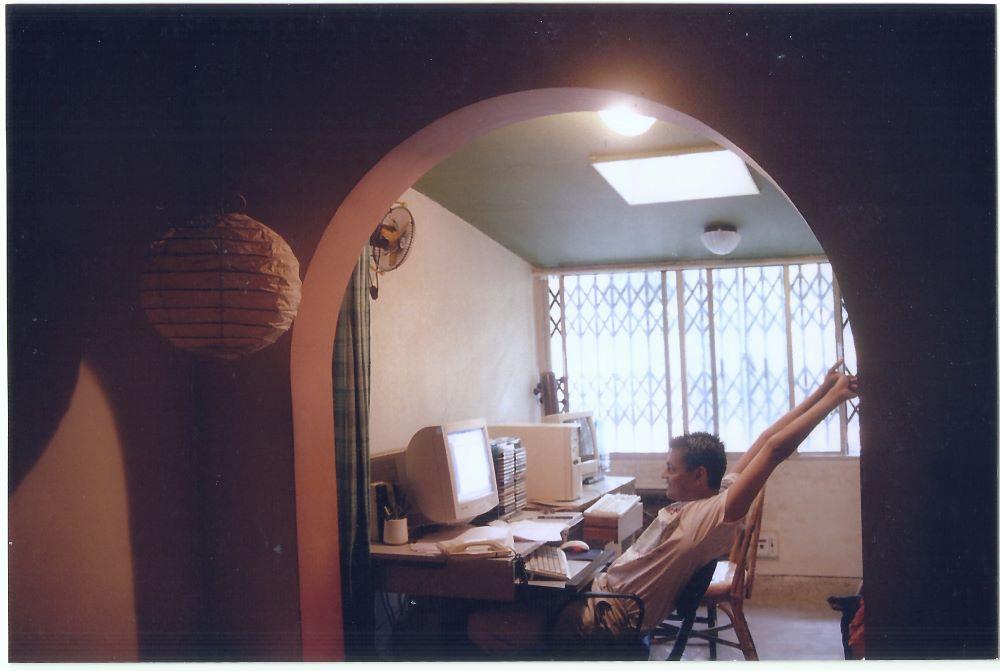

Still from Lovely Villa. (Avijit Mukul Kishore and Rohan Shivkumar. India. 2019. 32 minutes. Image courtesy of the artists.)

Shivkumar is an architect and scholar, and it is his home and family that we gradually get to know. In the final act of the documentary, we witness the illness and death of his father, a loss that the family grapples with. Those who remain—a mother and two siblings— take a trek together, and we can recognise this as a familiar ritual, a way to hold on to one another in the face of loss. The script entwines the dual approach of the documentary—a lyrical-meditative narration by Sonal Sundaranjan is balanced by the more staid, expository tone of Shivkumar and collaborator Avijit Mukul Kishore. It reminds you that while there may be innumerable ways to read a family and thus, a house, there never is simply just one.

Still from Lovely Villa. (Avijit Mukul Kishore and Rohan Shivkumar. India. 2019. 32 minutes. Image courtesy of the artists.)

What Lovely Villa introduces—and this has been explored in greater detail in another documentary by Shivkumar and Kishore, titled Nostalgia for the Future (2017)—is the idea that selfhood and habitat are inseparable phenomena. In the modern city, the laboratory for civic sensibility is the house unit. Jawaharlal Nehru’s opening remarks at the International Exhibition on Low-cost Housing held in New Delhi in 1953 make this point clear: “A house is not merely a place to take shelter from the rain or the cold or the sun. It is, or should be, an enlargement of one’s personality, and if human welfare is our objective, this is bound up with the house”. If the seventeenth century’s anamorphic vision of sovereign power is captured in Abraham Bosse’s etching of Leviathan—a large monarchic body comprising smaller figures—the twentieth century drums up the city master plan, where controlled and ordered landscapes of habitation are divided into plots, houses and tenements.

Still from Nostalgia for the Future, featuring a young Rohan Shivkumar. (Avijit Mukul Kishore and Rohan Shivkumar. India. 2017. 54 minutes. Images courtesy of the artists.)

The 1950s witnessed the central government take up the crisis of urban housing while delegating the provision of rural housing to state governments. A spate of governmental programmes and institutions were created, notably the National Buildings Organisation (1954) in Delhi, to research low-cost housing techniques and materials that would achieve mass housing schemes. The Hindustan Housing Factory, a company established in 1950, which also absorbed the previously existing department Hindustan Prefab Limited (1948), soon shifted to a part-public ownership model, and was leased to private parties. Recurrent losses led to dissolution of the lease in two years, and the Factory returned to being fully state-owned in 1955. Urban planner, architect and one of the founding editors of Marg magazine, Otto Koenigsberger, led the creation of the Factory. Its centre in Delhi’s Jangpura has a railway track running through it so that parts could be shipped easily. A film by Pratap Parmar, snippets of which appear in Nostalgia for the Future, titled Housing for the People (1972) narrates the journey of urban housing in India. The narrator stresses that “... a day may come when every Indian family will live with dignity in a separate self-contained unit”. With the use of materials such as precast aerated concrete, this is precisely what the Factory manufactured: single-storeyed units comprising two- bedroom houses. These houses were intended to shelter refugees who arrived in Delhi during the Partition. The concrete in early models produced under Koenigsberger’s supervision fell apart, with cracks and collapses making the units unsafe. A massive public scandal (the “prefab scandal”) saw the departure of Koenigsberger, but the production of housing units with treated concrete continued.

Still from Nostalgia for the Future, featuring the Lakshmi Vilas Palace in Baroda. (Avijit Mukul Kishore and Rohan Shivkumar. India. 2017. 54 minutes. Images courtesy of the artists.)

Nostalgia for the Future focuses on four structures—the Lakshmi Vilas Palace in Baroda; Villa Shodhan, a private residence designed by Le Corbusier in Ahmedabad; the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad; and the refugee resettlement colony built by the Delhi Development Authority in New Delhi. Shot in a style that film critic Nandini Ramnath describes as the “architecture of the classic Films Division documentary,” it uses the techniques of omniscient narration (by Avijit Mukul Kishore), a black-and-white template and grainy effects on colour footage to impress upon us the educational nature of such films. In interviews both Kishore and Shivkumar have stressed that they are interested in the idea of the civic body as it unfolded in India through various architectural expressions.

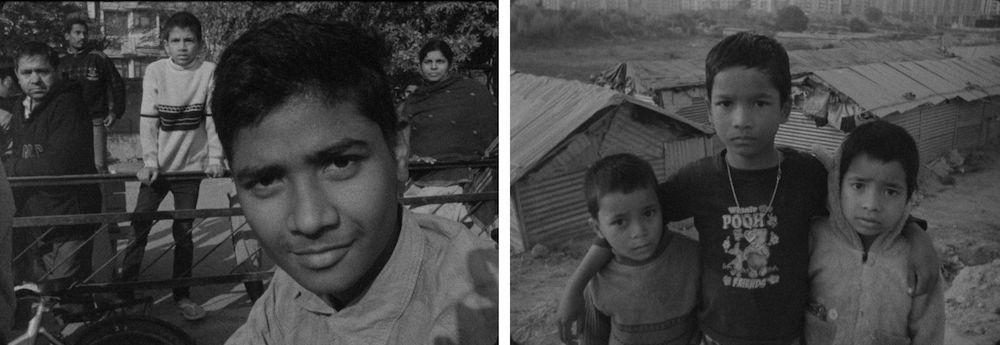

Stills from Nostalgia for the Future. A key moment the film dwells upon is that of post-independence Delhi, designed by the Government of India to house refugees from Pakistan. (Avijit Mukul Kishore and Rohan Shivkumar. India. 2017. 54 minutes. Images courtesy of the artists.)

The last of the four buildings foregrounds with searing precision the contemporary questions of life in the neoliberal state, the ideas of citizenship and the rights of the persons seeking asylum. The issues of refuge and resettlement burn through our times and across territories, as vividly and urgently as they did in the 1950s, when half a million refugees fled to Delhi. Housing schemes had expanded the orbit of the city exponentially: colonies in Vijay Nagar, Model Town, GTB Nagar and villages along Jangpura and Nizamuddin were planned and unplanned currents running alongside one another in an effort to not only offer asylum but a stake in life. The refugee colonies of New Delhi depicted in Nostalgia for the Future present the twin sides of the vision of a welfare state and its unruly trajectories. The tenements and colonies, designed as “rows of small, identical units,” were “modest in a practical, intentional way”. While the cheaply constructed small houses and tenements were a far cry from the ideal projections of a modern home, they illustrate what anthropologist Erin Riggs describes as possible “when a government grants legal status to a large population of dispossessed people”. The narrative of the enterprising refugee building a “new” Delhi haunts the empty, discarded houses. Today, there is a stark divide between colonies deemed legitimate, and those on the verge of being dismantled. News of arbitrary demolitions, sealings, promises of freehold and ownership or reconstruction shadow refugee colonies that have survived the onslaught of clearance and evictions.

Still from Nostalgia for the Future featuring a rickshaw-puller in Delhi. (Avijit Mukul Kishore and Rohan Shivkumar. India. 2017. 54 minutes. Images courtesy of the artists.)

Those arriving in New Delhi in search of opportunities since the late 1970s have settled into informal colonies and bastis; the Nagla Machi on the side of the Yamuna River is one of them. Bastis live on the verge of being razed at a whim of the governing municipal body. In 2006, Nagla Machi saw the demolition of over 12,000–15,000 households. In Trickster City: Writings from the Belly of the Metropolis (2010), author Jaanu Nagar describes the eerie aftermath of demolitions in Nagla Machi: “When evening falls, a strange pall descends over Nagla. With so many houses broken, even the mosquitoes have become homeless and they roam around freely, entering the houses still standing”. All that remains of the basti is a barren field. Each time I cross what once used to be Nagla Machi, I think of what the city and its governing bodies give to the people arriving today. Those in parts of eastern India are being trapped in detention centres, with the construction of more such centres underway to hold “illegal immigrants”. When tasked with thinking about whether we would have assisted asylum seekers in the Second World War, the necessary task is to also think about what we are doing today. Who has the right to the city? And where does the city end?

To read more about the work of filmmaker Avijit Mukul Kishore, please click here.

To read more about modernism and architecture in New Delhi, please click here.