Against Forgetting: Family Albums of Disappeared Persons

Remembering is a political act in regions of conflict, where free press is suppressed—including information about the heinous violence administered by the state on its citizens. Working closely with the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), Siva Sai Jeevanantham accessed case files and photographs of enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings and state-sponsored torture, along with family photo albums in the highly militarised state of Kashmir to put together his series In the Same River. Currently on view as part of the Chennai Photo Biennale, the work is also driven by an understanding of the resonance between the context of Kashmir and the struggle for Tamil Eelam. In the following conversation, Jeevanantham outlines the scope of this project and his methodological premises.

Sukanya Deb (SD): Could you tell me a bit about your research methodology and how you came across the families and their photo albums which are a part of this project?

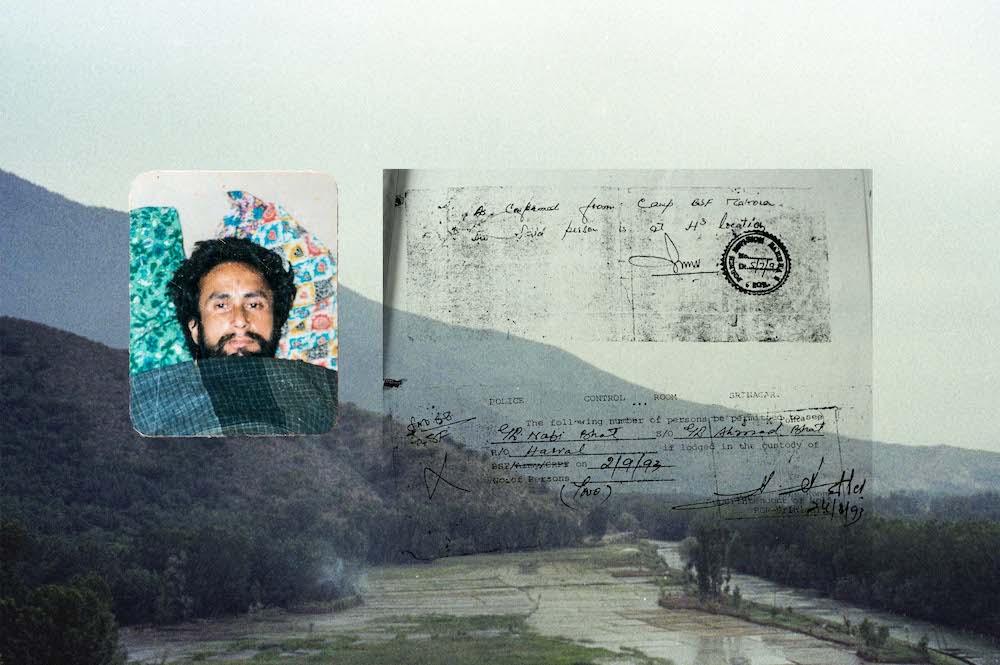

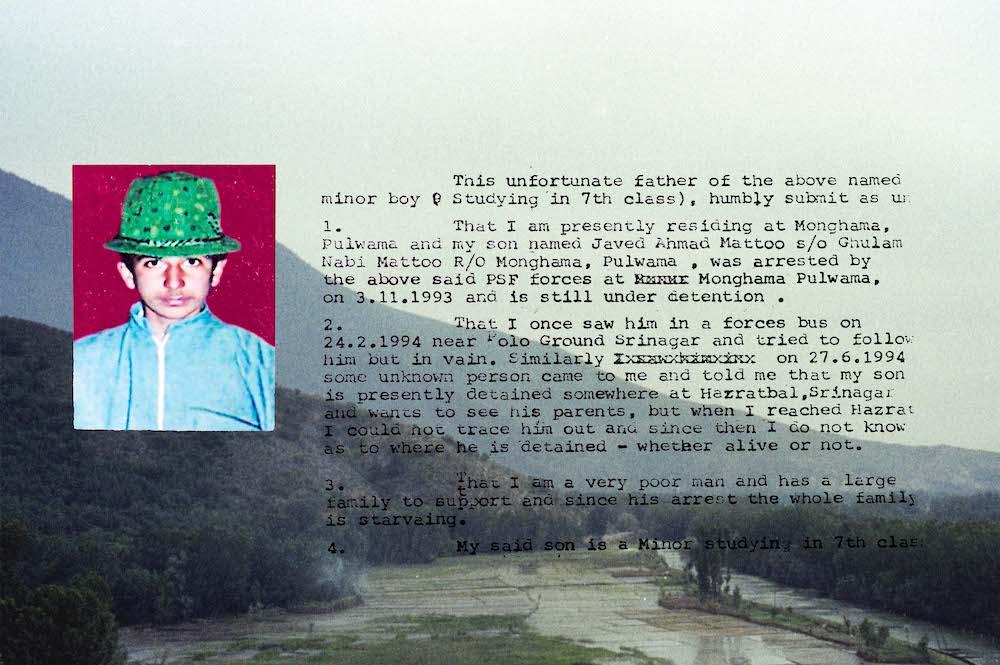

Siva Sai Jeevanantham (SSJ): While I was a student at National Institute of Design (NID), I was doing an internship with Kashmir Ink, which I had been unable to pursue earlier due to curfews in the state. During this period, I came to know of the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP). In the next year, I started working as a research assistant there. I began by collecting photographs from the APDP files, and trying to understand their process of archiving. This was during the time of my NID dissertation, for which we had been asked to trace Indian history through photographs. I wanted the APDP archive to be a part of this: as an untold Indian history, which the government does not want to speak about. I worked on the project for many years, and the files at the APDP office became my starting point. Many families used to come to the APDP office, and with the files within my reach, I selected families that were safer to go to (who were not as vulnerable to existing police investigations). I would take this forward to the resource manager to see which were the most severe cases, and she would guide me in terms of the procedures around travelling and making contact with the family. So, when I visited the families, the team and I conducted interviews and collected photographs. In Kashmir’s context, people are ready to talk to outsiders in the hope that their cause will be magnified. I sometimes ended up living with the families for two-three days as one could only come out when the army was not in the area. Half of my work comes from the APDP case files, where there were stories of mass graves or torture sites. I traced back the stories and went to the sites. When there were no photographs available, often family albums are used as reference, where images are cut out to be pasted onto the investigation document.

SD: What role does the family album play in your work? I can see that you are responding to a certain lack of evidence, and perhaps the family album provides key insights into the nature of occupation.

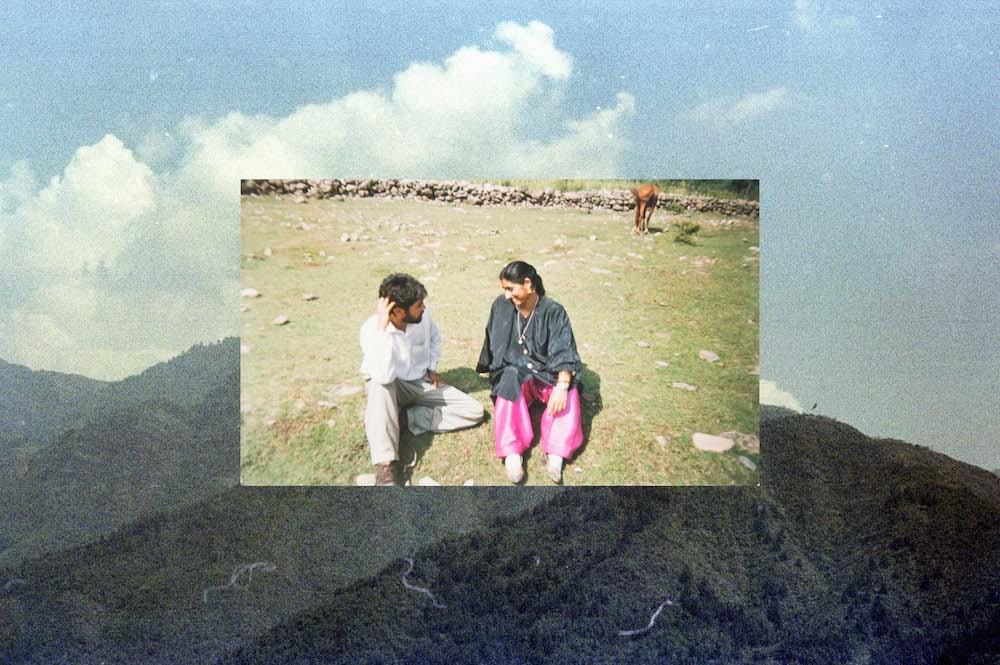

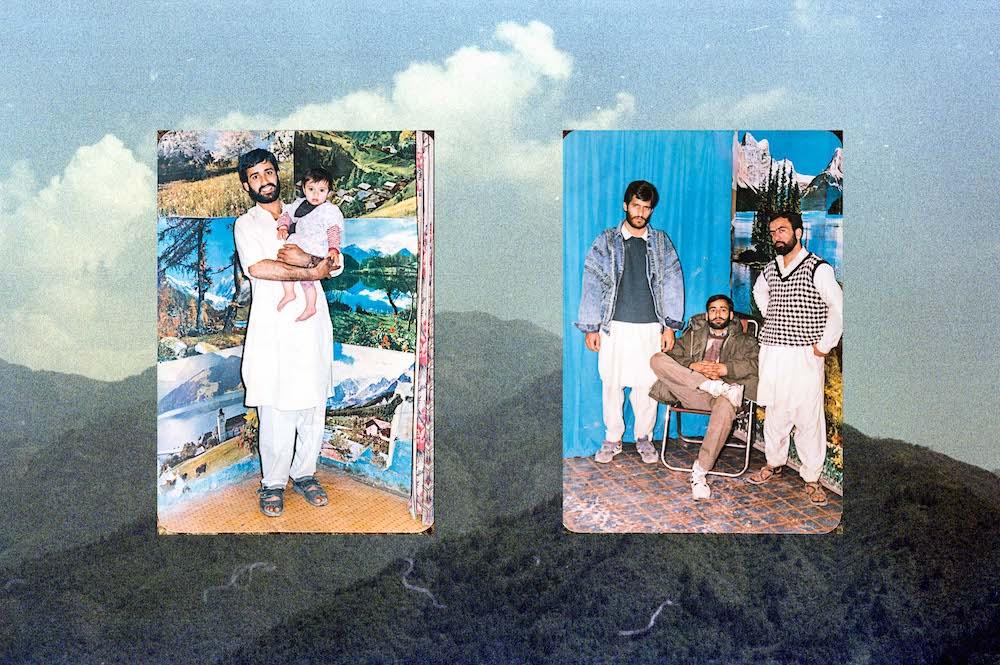

SSJ: There was this idea of remembrance, but a certain redundancy was taking over the photographs of the families that I visited. They wanted to remember the missing person so they made these cutouts of the particular person from the period when he died. They started photoshopping these into the current family photographs and talked about the memory that went with the photographs. Remembering becomes an important part of the whole APDP movement, with family portraits and albums becoming a very important aspect for the single prints. These family photographs become a very personal thing in people’s homes.

Another important part was that the family photographs were becoming a proof of their existence, to get explanations and compensation from the Jammu and Kashmir State Human Rights Commission (disbanded after the Abrogation of Jammu and Kashmir in 2019). There was a family that I visited, where everyone including the mother had a photograph taken for the purpose of proving that they are the descendants or heirs of the missing person, beyond which they did not even have a proper family portrait. In a place of conflict, the line between the family album and the family portrait is sort of fading.

All images from In the Same River by Siva Sai Jeevanantham. Kashmir, 2017-21. Images courtesy of the artist and Chennai Photo Biennale.

To read more about the third edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale, please click here, here and here.