Ways of Being (In a City): Review of Delhi: Looking Out/Looking In

In the summer of 2021, Aperture magazine published a volume titled Delhi: Looking Out/Looking In, guest-edited by curator Rahaab Allana. Extending a thematic of the city as site from previous issues and with contributions on resistance and retrospection; Delhi: Looking Out/Looking In silhouettes image-making and urban assertions of belonging against imaginations from within and outside the city of Delhi. Across essays by Latika Gupta, Kaiwan Mehta and Sabeena Gadihoke featured in this issue of Aperture, I read ways of living, remembering and seeing—in Delhi and beyond—emerging out of and alongside a genealogy of subcontinental futurity.

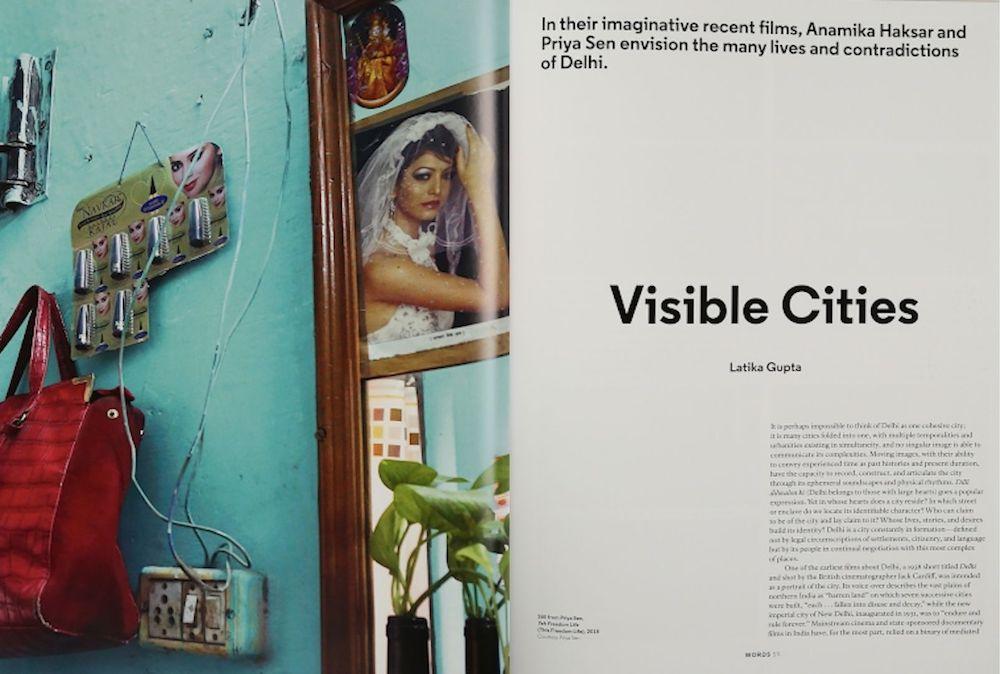

Yeh Freedom Life alternates between the two vastly different worlds of Sachi and Parveen. They are both in love with other women, and the film follows their search for "freedom lives," away from societal scrutiny and expectation. (Priya Sen. Yeh Freedom Life. New Delhi, 2018. Seventy Minutes.)

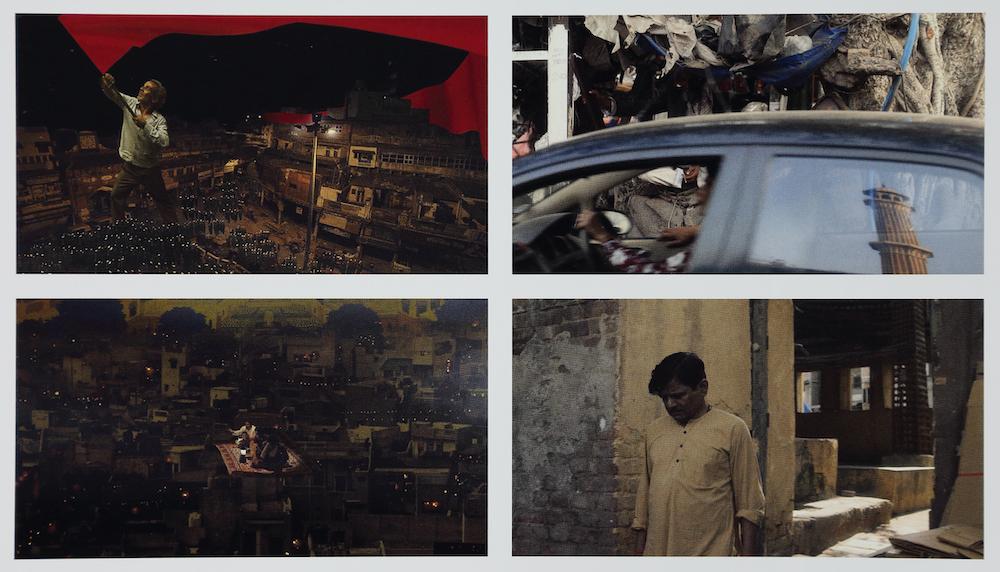

In “Visible Cities,” Latika Gupta begins with a proposition: Delhi is a city constantly in formation, always growing, negotiating and reifying. Gupta’s analysis of moving image explorations in Delhi captures two sets of familiarities with the city, evident in the films of Anamika Haksar and Priya Sen. Haksar's genre-defying Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Ja Riya Hoon (Taking the Horse to Eat Jalebis) builds on the fictions of Delhi's past that anchor it to its present. Her use of technical, social and ideological approaches pertaining to the direct cinema genre coupled with theatrical mise-en-scene follows various strata in the fraught city. She particularly acknowledges the painfully pragmatic lives of migrants through the absurd insertions of dreams and nightmares. Gupta notes the intersectionalities of caste, class and gender that Haksar addresses, especially in the way she represents the illegality of aspirations and the violence of urban life at the margins of a city like Delhi.

Gupta also refers to two films by Sen—Noon Day Dispensary (2014) and Yeh Freedom Life (This Freedom Life, 2018). The former looks at what it might mean to “resettle” within the expanse of a city while the latter interrogates what it might mean to “inhabit” interstitial spaces within one. Both films frame the tensions of precarity and fragility; Sen is observationally aware of what she enables as an image-maker and maps the microlocality as a complex space occupied by multiple densities of religion, gender and class. Gupta’s readings of both Haksar and Sen are imbued with her own experiences of the contradictions that Delhi straddles, and she returns continually to her primary argument: Delhi is made anew with each dissenting claim to belonging, with each gathering. In its collectivity, the city is neither spectacle nor nostalgia, but a fiery recalcitrance of both.

The result of a seven-year-long documentation of the lives of the people of Old Delhi, Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Ja Riya Hoon follows four main characters: a pickpocket, a vendor of sweet and savoury snacks, a labourer-activist, and a conductor of “Heritage Walks.” (Anamika Haksar. Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Ja Riya Hoon. New Delhi, 2018. Two Hours Two Minutes.)

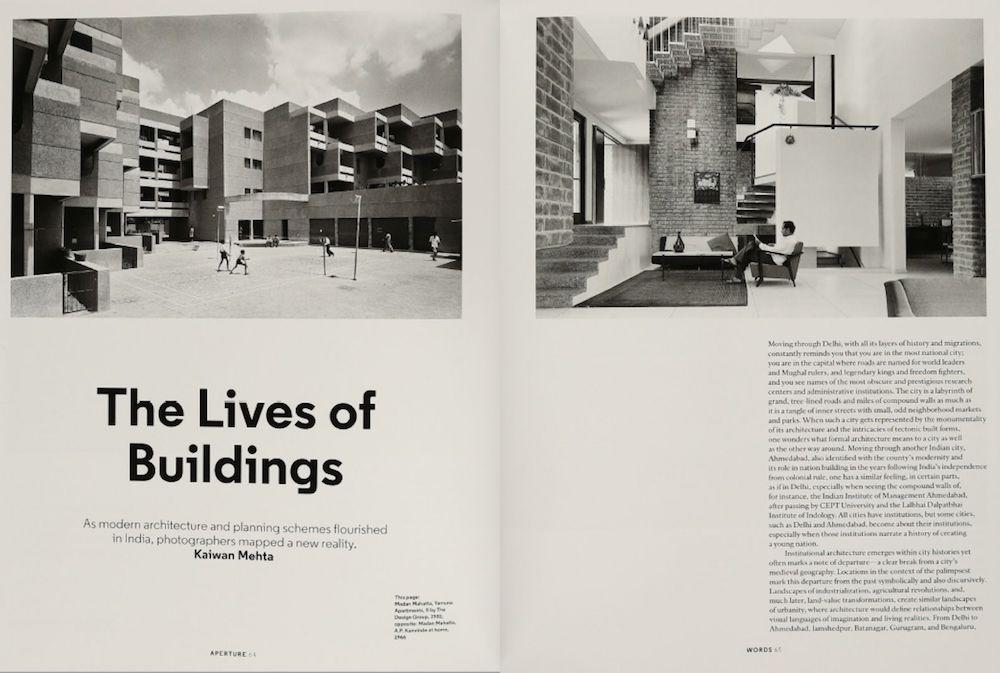

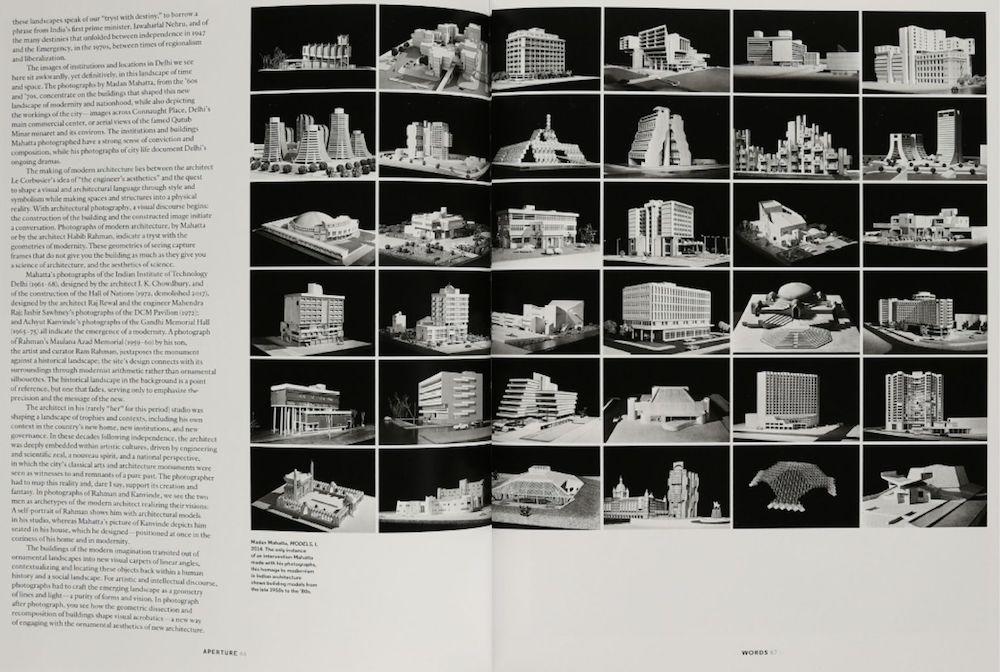

Looking at how institutional architecture in India has been imaged over the years through the photographs of Madan Mahatta, Ram Rahman, Akshay Mahajan and Rajesh Vora; Kaiwan Mehta traces a history of modernity and nationhood through built structures, following modes of remembering enabled by the medium of photography. Mehta notes the way Mahatta framed the geometry of iconic buildings along with abstractions favoured by their architects. He foregrounds these structures against the historicity of their locations, hinting at an inevitability: history fades and novelty is re-emphasised as want. Wondering about the monumentality of architectural form, Mehta studies the affectivity of lived space and material decay in the photographs taken by Mahajan and Vora, identifying new languages of built form and vocabularies of image composition. Adding to and altering public imaginations, he views photography as merging the real with the fabricated, just as modernist architecture in India offers a retrospective of a failed Nehruvian liberal utopia.

Left: Yamuna Apartments, II by the Design Group. In Mahatta’s photographs of institutional architecture, there is a definitive triumph of a new visual language seeking to establish itself and the image of a modern, developing nation. (Madan Mahatta. 1981.)

Right: Achyut Kanvinde at Home. The architects of these visions of a modern India—Achyut Kanvinde, Habib Rahman, Raj Rewal etc.—were not far removed from the structures they built. (Madan Mahatta. 1966.)

Models, I. Tracing the making of modern architecture through photography, Mehta notes Mahatta’s manner of encountering architecture and conveying its dimensionality to the viewer, unbothered by the flattening afforded by the medium of photography. (Madan Mahatta. 2014.)

The Illustrated Weekly of India was a cosmopolitan magazine, imaging and imagining post-independence India. It was partial to conventions of pictorialist aesthetics as well as informal, amateur image-making practices. Sabeena Gadihoke’s essay, “The Printed World,” follows the evolution of the weekly’s stylistic expanse in the decades of the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, addressing the rise of video news cassettes and satellite television as reasons for its demise in 1993. In charting this trajectory, she highlights the magazine’s role in furthering the culture—practice, viewership and appreciation—of photography within the subcontinent. She also invites the reader to pay heed to the colonial inheritances the magazine espoused in its early years, especially with regard to certain reformist and elitist perspectives on dissent and hygiene.

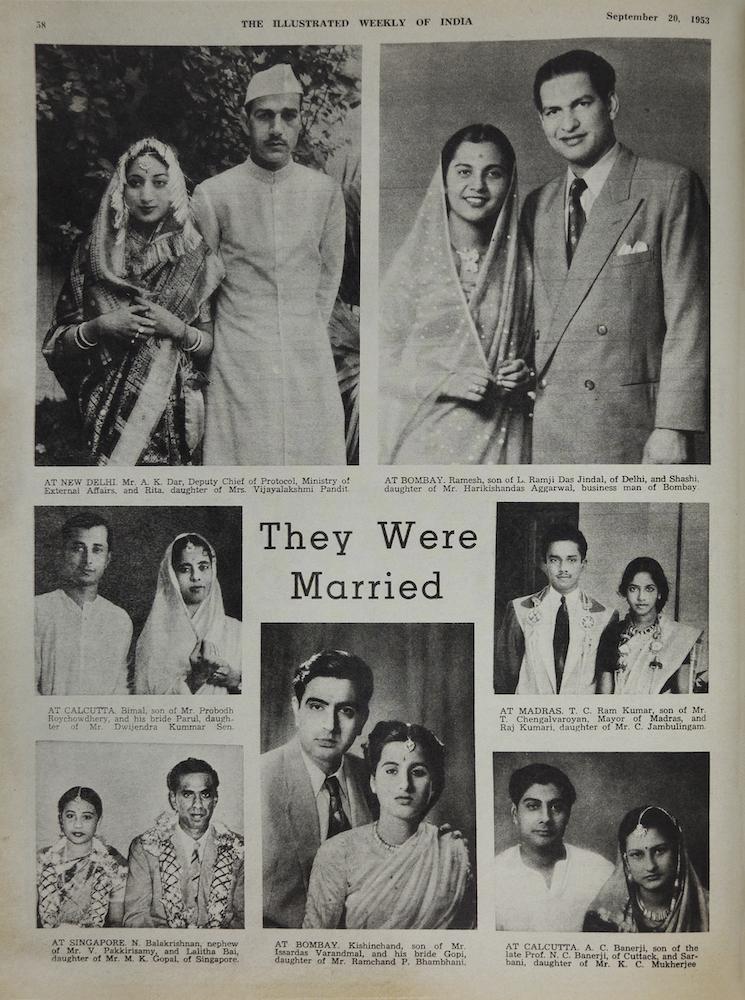

They Were Married (Feature). A popular section of the weekly featured studio portraits of newly wedded Indian couples from across the country and abroad. Drawing from its diverse readership, the section represented India’s rich ethnic diversity. (Illustrated Weekly of India. 20 September 1953.)

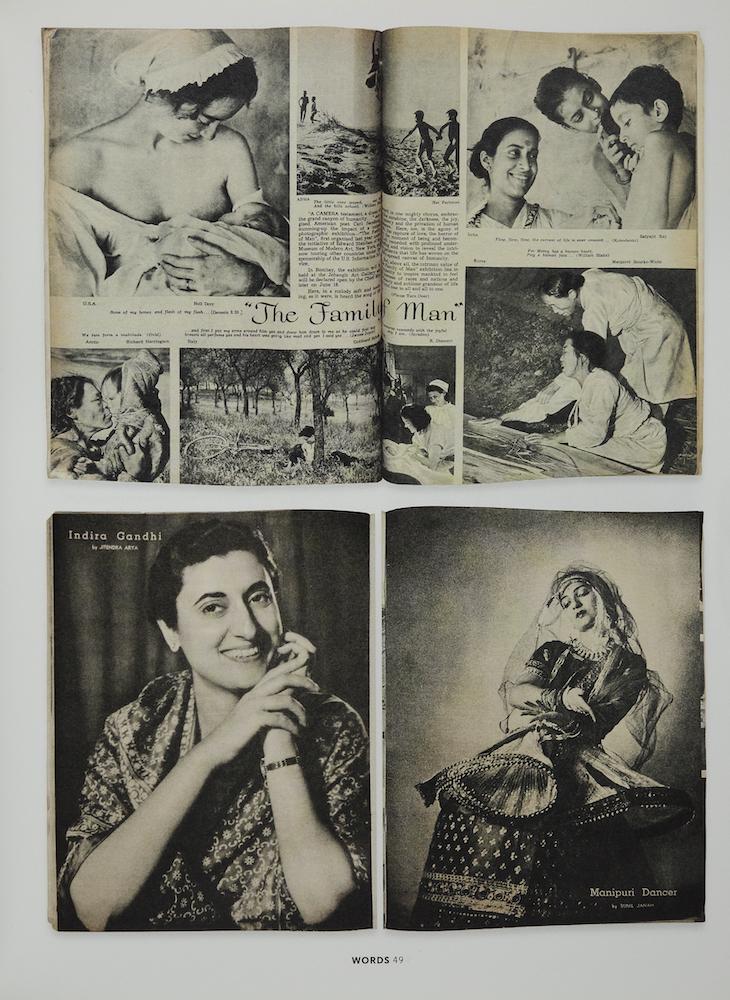

The Illustrated Weekly published some of the photographs from the exhibit the Family of Man, including the only Indian entry by filmmaker Satyajit Ray. (Illustrated Weekly of India. 3 June 1956.) Additionally, it also featured work by photographers from drastically different genres such as Jitendra Arya and Sunil Janah. (Illustrated Weekly of India. 23 August 1953.)

The space that it created for photography acknowledged the existence of its diverse readership. Gadihoke mentions how it included informal tutorials on photography and open snapshot competitions on various themes. It also paid attention to visibilising the early practices of photographers like Raghu Rai, Pramod Pushkarna and Kishor Parekh, who came to represent a new crop of independent photojournalists. In the content it chose to publish, the Illustrated Weekly structured exposure to novel ways of seeing from around the world, inspiring many who read it. Thinking of narratives outside of the mainstream, the magazine formed its readership base by inviting India to consider the many worlds outside and within its borders. A compilation of such multiple encounters, Delhi: Looking Out/Looking In is a shared imaginary of interrelationships, of micro- and macrocosmic imaginations, creating continuities and bridging gaps across space, time and frames. In the witnessing that occurs within its pages, the issue captures a city taking shape as story, journey, genre and infinity. Unfolding in the present, it invites readers to reside in—and identify with—an unyielding persistence of community fostered in the face of imminent erasure.

All images from Delhi: Looking Out/Looking In, guest-edited by Rahaab Allana. New York: Aperture Issue 243. Summer 2021. Images courtesy of Aperture.