A Living Archive: The Fifth Wall and Feminist Archiving Practices

On the evening of 3 April 2023, the Sher-Gil Sundaram Arts Foundation (SSAF) in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut conducted an event at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, titled “Navina Sundaram: An Outsider’s Inside View or an Insider’s Outside View.” Part of a series of events across Delhi, Bengaluru, Pune, and Mumbai, the event highlighted The Fifth Wall, a digital archive of reportage, commentary, films, personal correspondence and photographs from Navina Sundaram’s oeuvre, from the early 1960s to the late 1990s. Apart from a walkthrough of the website with one of the founders, Merle Kröger, along with a significant collaborator, Rubaica Jaliwala, the evening also included a screening of Sundaram’s documentary project, Behind Every Curtain (1989). This was followed by a discussion between Anuradha Kapur, Madhusree Dutta, and A. Mangai, moderated by Bishnupriya Dutt.

Merle Kröger and Rubaica Jaliwala introducing the website and conducting a walkthrough for the audience. (Image courtesy of the author)

Conceptualised by Merle Kröger and Mareike Bernien, along with Navina Sundaram, within the framework of Archive außer sich (Archives Beside Themselves), The Fifth Wall proposes itself as a model for future archival practice. The demise, on 29 March, of artist and activist Vivan Sundaram, who co-founded SSAF with Navina Sundaram, days before the event, lent a poignant tone to the evening, bringing the themes of remembrance and memory to the fore. In his introduction to the event, eminent film scholar Ashish Rajadhyaksha highlighted these ideas, speaking sensitively of Vivan Sundaram’s work with the living presence of the archive in our present time. As the enduring afterlives of past events were held up for examination, mourning and celebration were brought together as disparate yet coterminous experiences.

Professor Bishnupriya Dutt moderating the conversation between the three panelists.

The first woman of colour in German newsrooms, Navina Sundaram worked for North German Radio and Television in Hamburg in various roles from 1970 until her retirement in 2005. Given that Sundaram’s work is located at the interstices of feminism, postcoloniality and critical media, The Fifth Wall presents an interesting example of new practices for engaging with archival material. The act of creating an archive is a political one. It involves the selection of material at the expense of other data, announcing the importance of the material included. In this light, the choice to include Sundaram’s personal correspondence—brought to life by Jaliwala’s narration—as well as the platform’s free registration (to safeguard the space of the archive) gain importance. Moreover, the event itself, involving academics, practitioners, and activists, brings the archive to life, grounding its material within contemporary political and activist contexts.

As both Kröger and Jaliwala emphasised, The Fifth Wall is meant to be an archive that is used. This claim demands further attention. An archive is made usable by its openness to being searched—a quality that marks most archival efforts with a rigid, standardised cohesion devoid of any affective charge. In many ways, The Fifth Wall resists this inexorable pull, foremost through its emphasis on community involvement in the archive. As an exercise in digital historiography, the archive has the potential to reshape how academic practice is thought of, particularly in its efforts to distribute authorship. Jaliwala spoke of how this is reflected in the very design of the website as a mosaic; fragments of memory come together on the screen while objects and artifacts are interrupted by blank spaces, pointing to the nature of the archive as fragmentary, ruptured and always in process.

Anuradha Kapur directing rehearsals in Behind Every Curtain. (Image courtesy of The Fifth Wall: Navina Sundaram [die-fuenfte-wand.de/], © pong film GmbH / Navina Sundaram)

This radical vulnerability of the archive as a digital framework was brought home by the screening of Behind Every Curtain. Shot in 1989 at the Kasauli Art Centre, Sundaram’s documentary follows a theatre workshop through its inception, the fruition of the performance, and its many lives. The film depicts lively discussions that unfold between participants, including the likes of Anuradha Kapur (the director of the play), Madhusree Dutta, Urvashi Butalia, Sheba Chhachhi, Nivedita Menon, Nilima Sheikh, Geeta Kapur, and Anamika Haksar, among others. The performance comes together as a process, changing over the course of discussions held in the mornings and rehearsals in the evenings. Sundaram’s film, much like the archive, highlights a collaborative approach, made vulnerable and vibrant as a result of its distributed authorship. Further, the participation of Kapur and Dutta in the discussion that followed the screening carries forward the porosity of the film, stitching together the past and present.

Left to right: A. Mangai, Anuradha Kapur, and Madhusree Dutta in conversation following the screening of the film.

The archive, in a sense, brings the user into virtual proximity with the past that it documents. While such revisiting could prompt a sublimation of the performance’s political power into nostalgia, it can also present a model for radical continuity. In this manner, the performance can be born again in new bodies, as they witness its making on the screen. Through the archive, history can be prompted to “do” something and have effects or consequences in the contemporary political moment. For anyone accessing the archive, research becomes a “lived process”, charged with an affective dimension.

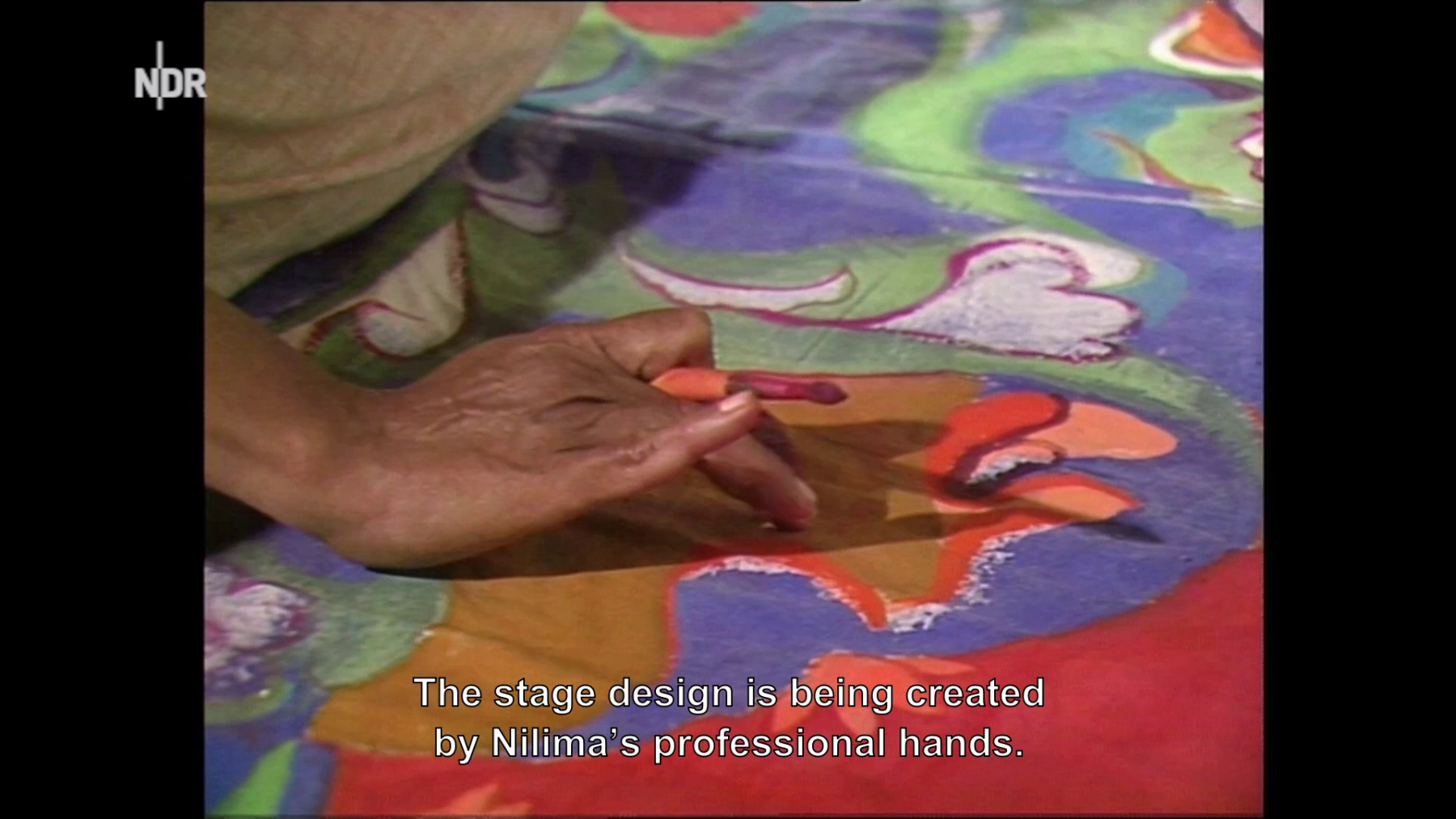

Nilima Sheikh’s efforts at imaging the lives of women, a practice she continued in collaboration with theatre, was documented by Sundaram in the film. (Image courtesy of The Fifth Wall)

This bent towards passionate scholarship is, of course, derived in part from Sundaram’s own feminist, intersectional practice of critical media, particularly in her documentation of South Asia for an international audience. Her operation outside the apparatus of Indian media history and her unique positionality as an insider/ outsider in German television define her work in the “borderlands”, as it were. Thus, her work and the process of archiving it for a future audience become important interventions in media history. While the archive indicates her situatedness in a genealogy of media practices in Germany looking to the Global South, the screening of Behind Every Curtain engenders the start of a genealogy of transregional feminist activism and performance in India. Turning the inquiry towards those inhabiting the present moment, Sundaram’s exercise in archiving the workshop’s many successes and failures in “figuring women” becomes a pedagogical one. The discursive roles of the workshop she documented, her film, and the event coalesce, engaging new scholars, practitioners and activists in a conversation that carries forward from then to now and into the utopic hope of what is to come.

To know more about The Fifth Wall, read Shivani Kasumra’s piece on the India launch of the archive, and Ankan Kazi’s piece on the launch of a few films from the archive in 2022, and his coverage of a talk detailing archiving collectives and practices. Watch Behind Every Curtain (1989) on The Fifth Wall archive.

All images courtesy of Sher-Gil Sundaram Arts Foundation unless mentioned otherwise.